Die Universität Konstanz hat einen kurzen Film zu meinem aktuellen Forschungsprojekt zum Thema “Staatenlosigkeit” gedreht.

Der Film kann auf dem youtube-Kanal der Universität Konstanz angeschaut werden.

Die Universität Konstanz hat einen kurzen Film zu meinem aktuellen Forschungsprojekt zum Thema “Staatenlosigkeit” gedreht.

Der Film kann auf dem youtube-Kanal der Universität Konstanz angeschaut werden.

In this invited lecture, I will discuss my concept of “we-formation” in regard to three different topics: First, as anthropological theory and methodology; Second, as a way to make sense of the resistance against the attempted military coup and third in regard to the possibility of a public anthropology of cooperation in these trying times.

First, I will explore the concept in regard to its theoretical and methodological innovativeness, taking an example from my Yangon ethnography as illustration. We-formation, I argue in my book Rethinking community in Myanmar. Practices of we-formation among Muslims and Hindus in urban Yangon, “springs from an individual’s pre-reflexive self-consciousness whereby the self is not (yet) taken as an intentional object” (8). The concept encompasses individual and intersubjective routines that can easily be overlooked” (20), as welll as more spectacular forms of intercorporeal co-existence and tacit cooperation.

By focusing on individuals and their bodily practices and experiences, as well as on discourses that do not explicitly invoke community but still centre around a we, we-formation sensitizes us to how a sense of we can emerge (Beyer 2023: 20).

Second, I will put my theoretical and methodological analysis of we-formation to work and offer an interpretation of why exactly the attempted military coup of 1 February 2021 is likely to fail (given that the so-called ‘international community’ does not continue making the situation worse). In the conclusion of my book I argue that the “generals’ illegal power grab has not only ended two decades of quasi-democratic rule, it has also united the population in novel ways. As an unintended consequence, it has opened up possibilities of we-formation and enabled new debates about the meaning of community beyond ethno-religious identity” (250).

Third, I will discuss how (not) to cooperate with Myanmar today. Focusing on what is already happening within the country and amongst Burmese activists in exile, but also what researchers of Myanmar from the Global North can do within their own countries of origin to make sure the resistance does not lose momentum. In this third aspect, I take we-formation out of its intercorporeal and pre-reflexive context in which I came to develop the concept during my fieldwork in Yangon and employ it to stress a type of informed anthropological action that, however, does not rely on having a common enemy or on gathering in a new form of ‘community’ that has become reflexive of itself. Rather, it aims at encouraging everyone to think of one’s own indidivual strengths, capabilities and possibilities and put them to work to support those fighting for a free Myanmar.

You can purchase my book on the publisher’s website: NIAS Press.

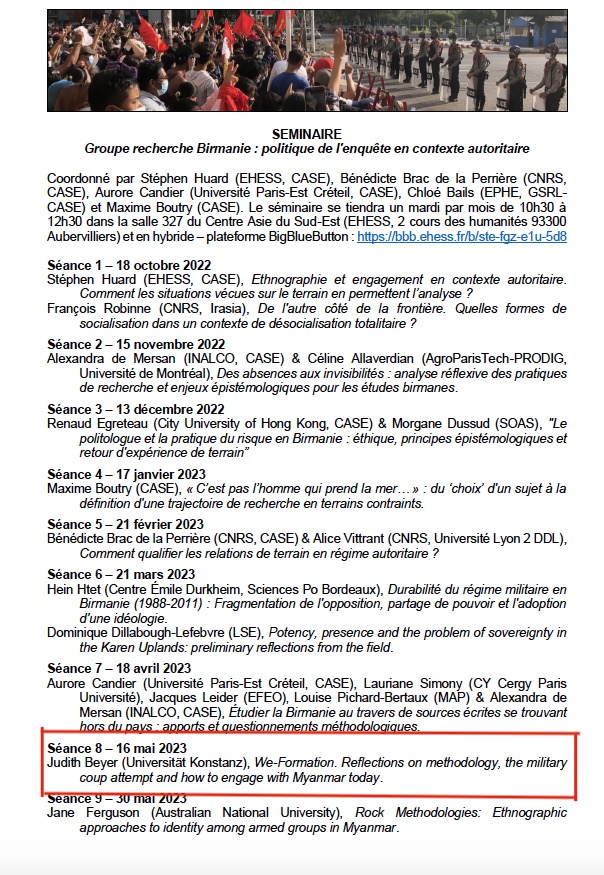

Here’s the full programme of the Groupe Recherche Birmanie for the spring term 2023:

‘Community’, I argue in my new anthropological monograph, was actively turned into a category for administrative purposes during the time of British imperial rule. It has been put to work to divide people into ethno-religious selves and others ever since.

Rather than bestowing on community some sort of positivist reality or deconstructing the category until nothing is left, my aim in this book is to shift the angle of approach: I acknowledge that community (for reasons that can usually be traced historically) feels real to and is meaningful for individuals. Their experiences and their struggles to engage with community are no less real. Through their own classificatory practices, my interlocutors — Muslims and Hindus in urban Yangon — demonstrate that they reason and reflect on symbols and meanings in their own culture as much as anthropologists do. But my approach goes beyond a social constructivist concern over how terms such as community are used, and also beyond a representational approach in which actors are subjected to culture as a system of meaning.

When I talk about the work of community (drawing on Nancy 2015), I reflect on the ways in which individuals accommodate ‘community’ in their acts of reasoning, meaning-making and symbolization. The way my interlocutors in Yangon see and talk about themselves has a historical context that begins in nineteenth-century England, encompasses British colonial India and later Burma itself, and extends into presentday

Myanmar. I then widen the emic perspective of my interlocutors and offer a novel way of describing how a we that does not neatly map onto or overlap with a homogeneous social group is generated in various situations.

What I call we-formation encompasses individual and intersubjective routines that can easily be overlooked, as well as more spectacular forms such as the intercorporeal aspects of the ritual march I described earlier. Attending to such sometimes minute moments of co-existence or tacit cooperation is difficult, but doing so can help us understand how community continues to have such an impact on the everyday lives of our interlocutors, not to mention on our own analytical ways of thinking about sociality.

By focusing on individuals and their bodily practices and experiences, as well as on discourses that do not explicitly invoke community but still centre around a we, we-formation sensitizes us to how a sense of we can emerge .

You can purchase the book on the publisher’s website: NIAS Press.

I published a new blog post for the Critical Statelessness Studies (CSS) Blog Series of the University of Melbourne.

I describe and analyse a central characteristic of many ‘expert activists’ working in the field of statelessness: they struggle with what I call a ‘practitioner-scholar dilemma’. Despite the fact that they often do cross disciplinary boundaries and fields of practice in combining scholarly and activist work, they position themselves on one side of an imagined divide. Drawing on Gramsci, I argue that the ‘practitioner-scholar dilemma’ originates in the way the state system structures the very possibilities of engagement with the issue of statelessness. I credit one newly emerging group of expert activists with the possibility to overcome this dilemma…

The article is accessible online on the CSS Blog serie’s website.

I published a new research article in Dialectical Anthropology as part of a (still forthcoming) special issue on Antonio Gramsci’s concept of “common sense”, co-edited by Jelena Tošić and Andreas Streinzer. The special issue will also feature an afterword by anthropologist Prof. Kate Crehan, an established Gramsci scholar and an important guiding voice during the virtual workshop that Jelena and Andreas organized and afterwards when we circulated our draft papers.

In the article, I follow a group of professionals in their efforts to address the problem of statelessness in Europe. My interlocutors divide the members of their group into “practitioners,” on the one hand, and “scholars” on the other. Relating this emic dichotomization to Antonio Gramsci’s dialectical take on common sense, I argue against a theoretical reductionism that regards expertise and activism as two essentially different and mostly separate endeavors, and put forward the concept of the “expert activist.” Unpacking what I call the “practitioner–scholar dilemma,” I show that in their effort to end statelessness, “practitioners” take a reformist route that aims at realizing citizenship for the stateless, while “scholars” are open to a more revolutionary path that contemplates the denaturalization and even the eradication of the state. By drawing on Gramsci, I suggest that the impasse the group encounters in their work might relate more to the structural constraints imposed by the state within or against which they operate than to the problem of statelessness they are trying to solve.

My article contributes to a body of emergent work in anthropology that explores the intersection of scholarly expertise and activism. It is also the first article that I am writing on the topic of statelessness, drawing on my new fieldwork data that includes written observations, photographs, the recording and subsequent transcription of free-flowing conversations, oral presentations and speeches, journal entries, and textual documents, all obtained from participating in workshops, conferences, and policy briefings in various European settings such as universities in the UK, museums, and event spaces in The Hague and at the European Youth Centre and the Council of Europe in Strasbourg.

My ethnographic research is ongoing and involves in-person and online attendance at thematic webinars on the topic of statelessness, in annual stakeholder meetings, and the launching of new reports and other publications.

I am particularly interested in receiving feedback from the people I have been working with as I continue researching the topic of expert activism and statelessness in Europe.

The article is currently accessible through open access on the journal’s website.

The Myanmar military will appear at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague on 21 February 2022. I argue that their main interest does not lie in defending the country against genocide allegations. Read the full post at Allegra Lab.

In the case of The Gambia vs Myanmar currently pending at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), Myanmar has been accused of having violated the UN Genocide Convention of 1948 by committing serious crimes against the Rohingya, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group. In 2017, 800.000 Rohingya fled Myanmar to neighbouring Bangladesh in an effort to escape the military’s atrocities.

The army’s attempted military coup of February 202

The case did not proceed after the Myanmar military attempted a coup on 1 February 2021. That night, Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint were arrested and have since been accused of corruption, violations of the telecoms law, a state secrets act as well as covid-19 regulations. They are currently facing several years of imprisonment. The generals declared the November 2020 parliamentary elections as fraudulent and put a state of emergency in place. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing is now heading the country. But not only the State Counsellor and the President, but the entire population of Myanmar has been held hostage: since February 2021, over 1.500 people have been murdered, thousands have been arrested and 450.000 people have become internally displaced, adding to the already high numbers of IDPs.

The National Unity Government

Members of the parliament elected in November 2020 formed the National Unity Government (NUG) while in hiding, now operating from undisclosed locations. They have established working relations with many states and international organizations, including the UN, where Ambassador U Kyaw Moe Tun supports the NUG and has been able to continue representing his country even though the military fired and charged him with high treason. While the military regime has received backing from China and Russia, most other countries have cut diplomatic and also economic ties with Myanmar under the current leadership. The question of who is representing Myanmar in the international community is a contested one which needs to be kept in mind when the case in The Hague continues on 21 February 2022.

Trying to benefit from a genocide accusation

Historically, the army has shown no interest in complying with international legal norms. The “rule of law”-paradigm has been a particular red rag for the Generals. Still, the Myanmar military will likely send delegates to attend the upcoming proceedings in The Hague. At the same time, the National Unity Government (NUG) has declared that United Nations Ambassador U Kyaw Moe Tun is the only person authorised to represent the country in The Hague.

However, for the generals, defending the country against the genocide accusation is largely a means to an end: they will use this opportunity to conduct themselves as the legitimate representatives of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar on a global stage. One should not fall for this trick, or not again: Already in April 2021 the military managed the feat that a general participated in an online-event of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), thereby bypassing the UN Secretary General’s own advice not to cooperate with the junta.

The ICJ is one of the principal legal organs for investigating violations of the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, to which Myanmar is a signatory. To invite the junta to represent the country means to offer them the chance to use the court as a platform for strategic litigation where no longer the crime, but the performance of legitimacy will be key: When the ICJ reopens the case against Myanmar, the Rohingya genocide is not a primary concern of the generals. Rather, it is to be ‘Myanmar’. The ICJ has a historical opportunity to avoid such an ethical, political and legal failure.

Read the full post at Allegra Lab.

Mit Tilman Seiler habe ich mich nun schon zum zweiten Mal über die Widerstandsbewegung in Myanmar unterhalten, die sich nach dem Militärputsch vom 1. Februar 2021 im ganzen Land gebildet hat. Er fragte, wie erfolgreich diese sei, wie fest im Sattel die “Putschregierung” sitzen würde und auch, was von der Ankündigung des Militärs zu halten sei, es werde Neuwahlen geben nachdem Min Aung Hlaing die im November 2020 stattgefundenen Parlamentswahlen für ungültig erklärt hatte. Meine Prognosen sind realistisch, also recht düster.

Ein zweites Thema betraf die Situation der Rohingya im weltgrößten Flüchtlingscamp in Bangladesh. Hier wollte Herr Seiler wissen, wie die Regierung des angrenzenden Nachbarstaats mit den Geflüchteten umgehen würde und auch, was die internationale Weltgemeinschaft tun könne, um die mittlerweile 1,5 Millionen Rohingya zu unterstützen. Ich berichtete von den laufenden Plänen Bangladeshs, circa 100.000 Rohingya auf die eine vorgelagerte künstliche Insel in der Bengalischen See zu verlagern und sagte auch, dass dies im großen Fall gegen den Willen der Menschen dort geschehe.

Darüber hinaus erinnerte ich daran, dass vor allem im Fall staatenloser Geflüchteter wir “bei uns vor der Haustür” mit der Unterstützung beginnen können, nämlich indem man das eigene Asylsystem reformiert, welches bei Staatenlosen in den meisten Fällen immer noch unzureichend greift: Menschen, die keine offiziellen Dokumente zu ihrer Identifikation vorweisen können, haben es hier besonders schwer.

Das zehnminütige Gespräch ist in der ARD alpha-Mediathek zu finden.

Together with Felix Girke I published an article in the German Journal of Law and Society / Zeitschrift für Rechtssoziologie as part of a special issue on the occasion of the journal’s 40-year anniversary.

Our article is a re-reading of the German anthropologist Gerd Spittler’s article “Dispute settlement in the shadow of Leviathan” (Streitschlichtung im Schatten des Leviathan) which was published in the journal in 1980 as part of the inaugural issue. In this article, Gerd Spittler strives to integrate the existence of state courts (the eponymous Leviathan’s shadow) in (post-)colonial Africa into the analysis on non-state court legal practices.

We walk the reader through his text (which has only been published in German) and then ask how has the situation he describes for (post-)colonial Africa in the early 1980s has changed in the last four decades. We relate his findings to contemporary debates in legal anthropology that investigate the relationship between disputing, law and the state. We also show through our own work in Africa and Asia, particularly in Southern Ethiopia and Kyrgyzstan in what ways Spittler’s by now classical contribution to the field of legal anthropology in 1980 can be made fruitful for a contemporary anthropology of the state at a time when not only (legal) anthropology has changed, but especially the way states deal with putatively “customary” forms of dispute settlement.

The article is currently accessible through open access on the journal’s website.

Hannah Arendt is one of the best-known political theorists of the 20th century. Her books and her theoretical arguments emerged in dialogue with ancient philosophers (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle) and modern German thinkers (Kant, Hegel), as well as with her own university teachers (Heidegger, Husserl, Jaspers). Arendt never saw herself as a philosopher, but as a theoretician of the political. The topics she dealt with are today more topical than ever before and her books are being read across disciplines.

Hannah Arendt wrote on totalitarianism, statelessness, human community, and freedom and responsibility. In her work she processed her own experience as a Jew in Germany, as a stateless person in World War II, as a migrant in the USA, as a woman in male-dominated academia and as an attentive observer of an increasingly globalized post-war world.

This semester I am teaching some of her main theoretical themes to a group of BA students at the University of Kontsanz. We will not only embed Arendt’s texts in their historical context, but also to think through and with her arguments using current examples — ranging from the covid pandemic to state terror in Myanmar. Hannah Arendt was interested in the basic conditions of human existence: whenever these are questioned or radically transformed, her work offers a fruitful starting point.

“Why read Hannah Arendt now?” (2018) asks the author Richard Bernstein in his recent book. Answer: because she is “the thinker of the hour” (according to the German translation of the book).

Here is the Syllabus to my course (in German).