Our collaborative article “Exiled Activists from Myanmar: Predicaments and Possibilities of Human Rights Activism from Abroad“, published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice (Oxford University Press), is finally out! 🎉

I am very proud of the work that my colleague Samia Akhter-Khan, my two Ph.D. students Sarah Riebel and Nickey Diamond, another author from Myanmar (who has to use a pseudonym for reasons of safety), as well as myself have managed to achieve under very difficult circumstances.

This article was born out of necessity to engage with the topic of exile. None of us had ever wanted to study yet alone experience this existential state of being. The empirical material we draw on in this article stems from autoethnographic accounts (Nickey Diamond and Demo Lulin), semi-structured interviews and conversations with around forty exiled activists currently residing in Thailand, the US, the UK, Austria, and Switzerland (Samia Akhter-Khan and myself) as well as extensive ethnographic work with exiled activists in Thailand (Sarah Riebel).

In this article, we put forward the concept of the ‘exiled activist’ to highlight the predicaments and the possibilities that practicing human rights activism from abroad bring with it. From our analysis, we have developed three so-called ‘practitioner points’ that might guide INGOs, NGOs, states and other bodies to properly relate to exiled activists from Myanmar. These are:

1. Develop trauma-informed support systems for exiled activists by integrating psychosocial care and peer-based mental health resources into human rights programming and diaspora organizing.

2. Adapt partnership models to accommodate the shifting positionality of exiled activists, recognizing their need for secure digital platforms, flexible funding, and shared decision-making across borders.

3. Acknowledge and navigate political divisions within diverse groups of exiled activists – such as differing views on the National League for Democracy, the military, or the Rohingya – by avoiding assumptions of unity and instead fostering inclusive collaboration that respects diverse activist trajectories and lived experiences.

We have made our article openaccess so that everyone is able to download it. Currently, we are working on a shorter version in Burmese/Myanma, to also allow those who do not speak English to read about this important topic.

Thank you to all exiled activists who have participated in this study, trusted us and shared their stories – and to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the support of scholars at risk over the last years!

Category Archives: refugees

Open Acess: “Asylum Interviews in the UK”. Published in Social Anthropology

My new article “Asylum Interviews in the UK. The problem of evidence and the possibility of applied anthropology” has just been published with Social Anthropology / Anthropologie Sociale (33/3: 51-65).

In this article, I interrogate the process how evidence is established in asylum procedure by engaging with anthropological and socio-legal literature on evidence and credibility assessments. Drawing on ethnomethodology, I analyse asylum interviews and show in what ways evidence can be understood as the result of an asymmetrical co-construction. As a result of this procedure, the individual applicant disappears and a ‘case’ is established.

Anthropologists who write country of origin reports based on such ‘case material’ for tribunals and courts can highlight the asymmetries in evidence-making and question the very categorisations through which the state operates. The article contributes to ongoing debates on the role of anthropologists and their knowledge as experts in court.

It is open access and can be downloaded here.

Boat is a man

2024 has been the deadliest year for migrants trying to cross the Channel in small boats to reach the UK, with 69 deaths reported (Refugee Council 2025). British politicians have been referring to the circumstances under which people migrate to the UK as “the small boat crisis“ and subsequently made a “small boat deal“ with countries such as Ruanda, to which they wanted to ship people to.

Before the Labour party came to power, they accused the Tories of “having lost control of small boat migration“. Now, that they are in power, they claim that there is “no nice or easy way of doing it“. Getting rid of people who came by boat…

But what if boat were a man?

I recently bought a small booklet filled with Walter Benjamin’s short stories. Tales out of loneliness is its subtitle. In it, there is a 1-page story entitled How the Boat was Invented and Why It Is Called ‘Boat‘. It follows a similar pattern as Benjamin’s short story on Why the elephant is called ‘elephant‘ that immediately precedes the story about the boat.

Here’s how Boat’s story goes:

Before all the other people, there lived one person and he was called Boat. He was the first person, as before him there was only an angel who transformed himself into a person, but that is another story.

So the man called Boat wanted to go on the water — you should know that back then there was a lot more water than today. He tied himself to some planks with ropes, a long plank along the belly, that was the keel. And he took a pointed cap of planks, which was, when he lay in the water, at the front — that was the prow. And he stretched out a leg behind him and navigated with it.

In this manner he lay on the water and navigated and rowed with his arms and moved very easily through the water with his plank cap, because it was pointed. Yes, that is how it was: the man Boat, the first man, made himself into a boat, with which one could travel on water.

And therefore — of course that is quite obvious — because he himself was called Boat, he named what he had made ‘boat‘. And that is why the boat is called ‘boat‘.

(Walter Benjamin, 26 September 1933; published posthumously)

The “small boats crisis” is Boat’s crisis, the crisis of man. This is the elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about. Because they do not know why the elephant is called ‘elephant‘ either.

Philosophy saves lives.

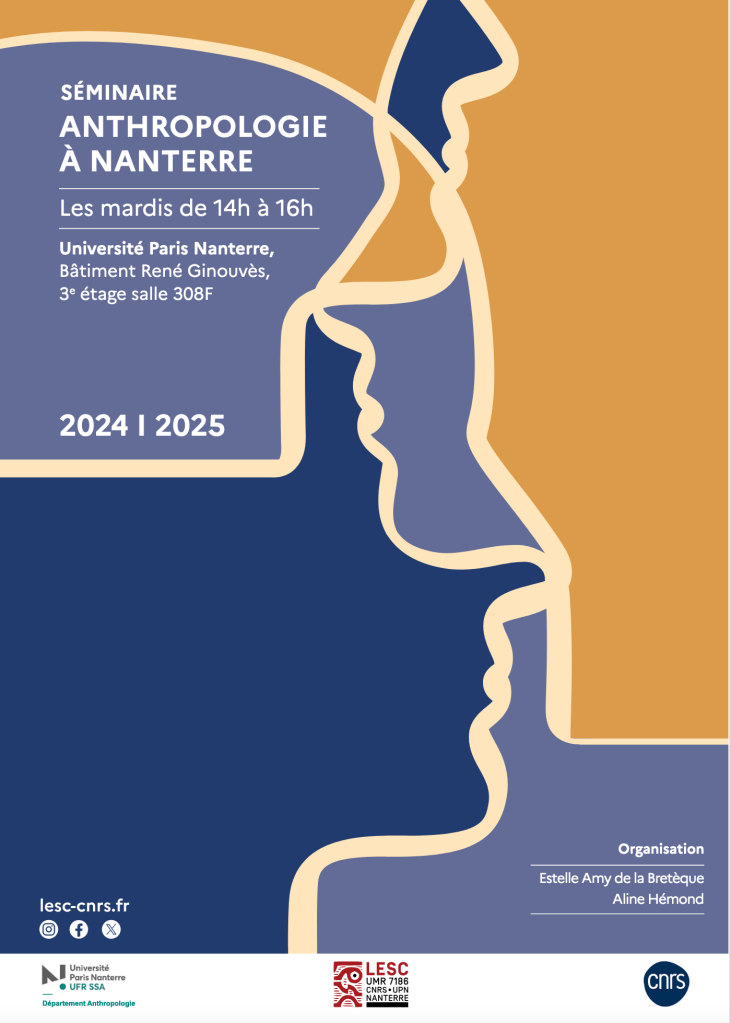

Research Colloquium at Université Paris-Nanterre

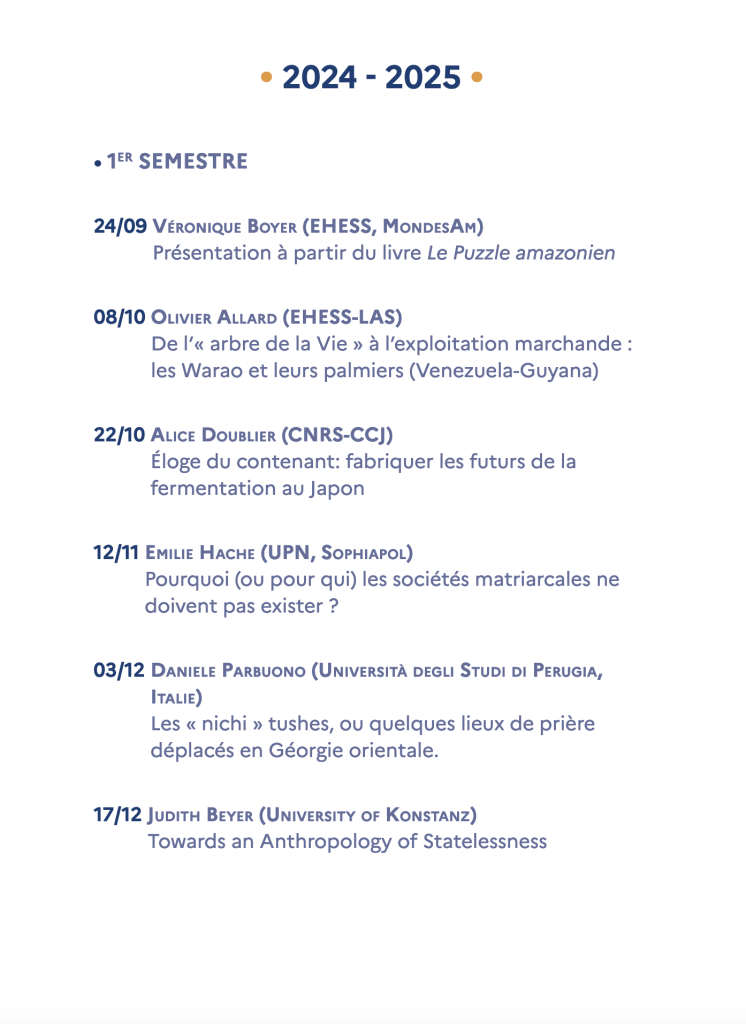

This winter term, I will be spending some time with my anthropology colleagues at Paris-Nanterre as part of the Laboratoire d’Ethnologie et de Sociologie comparative (LESC), part of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS).

One part of my research stay is devoted to working on my current project: “Towards an anthropology of statelessness”. I will be speaking at the Department’s Colloquium in December (see plan below). I will also be teaching a course in legal anthropology … more about this one later.

The colloquium is free and open to the public, everyone is welcome.

Come work with me! PhD positions on Europe

If you are a recent graduate (MA-/MPhil-degree holder) with an interest in pursuing a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology under my supervision, please consider applying for a PhD position at the newly established Graduate School “Post-Euroentric Europe. Narratives of a World-Province in Transformation” at the University of Konstanz.

Together with 10 other professors we have worked hard in the last years to realize an ambitious and highly relevant programme that is aimed at decentring and questioning narratives about Europe.

“Where is Europe?” we might be tempted to ask. “And is it even one place?” (Attali 1994). Is Europe to be found in the minds and hearts of the refugees detained in camps on its southern border, for whom it is place of longing, even as it denies them entry or sets up hurdles in their way? How and to what extent do “soft” cultural factors in the form of collective narratives and imaginations solidify into “hard” institutional realities, which in turn have a reflexive effect on the availability of narrative resources?

While it has long been customary to regard “Europe” and “modernity” as more or less synonymous, only recently has there been a systematic examination of the fact that the European continent was and is permeated by political-cultural demarcations and asyn-chronicities, even within its own borders. Increased attention to non-European traditions or those marginalized in Europe’s dominant self-narrative not only guides a redefinition of Europe’s position in world affairs; it also requires us to diversify notions of Europe from within.

The work of our graduate program aims to contribute to the historical and contemporary demonopolization of the concept of Europe in local contexts, which has been tightly restricted to dominant traditions in the West-Central European area.

Within this interdisciplinary Graduate School, I am particularly interested in supervising anthropological PhD projects with a focus on statelessness in Europe or its border regions or on one of the various European independence movements (e.g. in Catalonia, Bretagne, Basque Country, Scotland, Celtic Nationalism, One Tirol, … ). Other topics are possible, too, as long as they fit the programme and are based on ethnographic field research and lie within the field of political and legal anthropology.

Make sure you read the entire research programme carefully before preparing your application! If you have questions, contact me under my uni-konstanz email-address.The deadline is already 30 June 2024!

Film über meine Forschung: Staatenlosigkeit

Die Universität Konstanz hat einen kurzen Film zu meinem aktuellen Forschungsprojekt zum Thema “Staatenlosigkeit” gedreht.

Der Film kann auf dem youtube-Kanal der Universität Konstanz angeschaut werden.

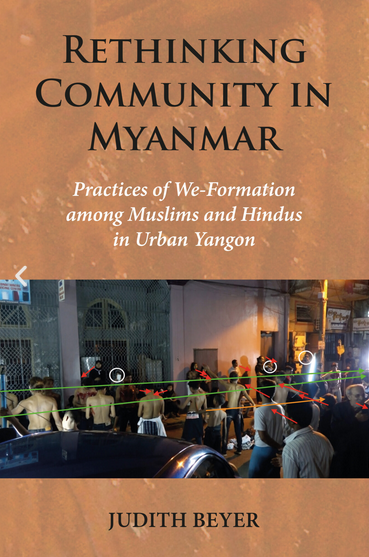

We-formation. Reflections on methodology, the military coup attempt and how to engage with Myanmar today. Lecture in Paris, 16 May 2023

In this invited lecture, I will discuss my concept of “we-formation” in regard to three different topics: First, as anthropological theory and methodology; Second, as a way to make sense of the resistance against the attempted military coup and third in regard to the possibility of a public anthropology of cooperation in these trying times.

First, I will explore the concept in regard to its theoretical and methodological innovativeness, taking an example from my Yangon ethnography as illustration. We-formation, I argue in my book Rethinking community in Myanmar. Practices of we-formation among Muslims and Hindus in urban Yangon, “springs from an individual’s pre-reflexive self-consciousness whereby the self is not (yet) taken as an intentional object” (8). The concept encompasses individual and intersubjective routines that can easily be overlooked” (20), as welll as more spectacular forms of intercorporeal co-existence and tacit cooperation.

By focusing on individuals and their bodily practices and experiences, as well as on discourses that do not explicitly invoke community but still centre around a we, we-formation sensitizes us to how a sense of we can emerge (Beyer 2023: 20).

Second, I will put my theoretical and methodological analysis of we-formation to work and offer an interpretation of why exactly the attempted military coup of 1 February 2021 is likely to fail (given that the so-called ‘international community’ does not continue making the situation worse). In the conclusion of my book I argue that the “generals’ illegal power grab has not only ended two decades of quasi-democratic rule, it has also united the population in novel ways. As an unintended consequence, it has opened up possibilities of we-formation and enabled new debates about the meaning of community beyond ethno-religious identity” (250).

Third, I will discuss how (not) to cooperate with Myanmar today. Focusing on what is already happening within the country and amongst Burmese activists in exile, but also what researchers of Myanmar from the Global North can do within their own countries of origin to make sure the resistance does not lose momentum. In this third aspect, I take we-formation out of its intercorporeal and pre-reflexive context in which I came to develop the concept during my fieldwork in Yangon and employ it to stress a type of informed anthropological action that, however, does not rely on having a common enemy or on gathering in a new form of ‘community’ that has become reflexive of itself. Rather, it aims at encouraging everyone to think of one’s own indidivual strengths, capabilities and possibilities and put them to work to support those fighting for a free Myanmar.

You can purchase my book on the publisher’s website: NIAS Press.

Here’s the full programme of the Groupe Recherche Birmanie for the spring term 2023:

Who gets to be ‘Myanmar’ at the ICJ?

The Myanmar military will appear at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague on 21 February 2022. I argue that their main interest does not lie in defending the country against genocide allegations. Read the full post at Allegra Lab.

In the case of The Gambia vs Myanmar currently pending at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), Myanmar has been accused of having violated the UN Genocide Convention of 1948 by committing serious crimes against the Rohingya, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group. In 2017, 800.000 Rohingya fled Myanmar to neighbouring Bangladesh in an effort to escape the military’s atrocities.

The army’s attempted military coup of February 202

The case did not proceed after the Myanmar military attempted a coup on 1 February 2021. That night, Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint were arrested and have since been accused of corruption, violations of the telecoms law, a state secrets act as well as covid-19 regulations. They are currently facing several years of imprisonment. The generals declared the November 2020 parliamentary elections as fraudulent and put a state of emergency in place. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing is now heading the country. But not only the State Counsellor and the President, but the entire population of Myanmar has been held hostage: since February 2021, over 1.500 people have been murdered, thousands have been arrested and 450.000 people have become internally displaced, adding to the already high numbers of IDPs.

The National Unity Government

Members of the parliament elected in November 2020 formed the National Unity Government (NUG) while in hiding, now operating from undisclosed locations. They have established working relations with many states and international organizations, including the UN, where Ambassador U Kyaw Moe Tun supports the NUG and has been able to continue representing his country even though the military fired and charged him with high treason. While the military regime has received backing from China and Russia, most other countries have cut diplomatic and also economic ties with Myanmar under the current leadership. The question of who is representing Myanmar in the international community is a contested one which needs to be kept in mind when the case in The Hague continues on 21 February 2022.

Trying to benefit from a genocide accusation

Historically, the army has shown no interest in complying with international legal norms. The “rule of law”-paradigm has been a particular red rag for the Generals. Still, the Myanmar military will likely send delegates to attend the upcoming proceedings in The Hague. At the same time, the National Unity Government (NUG) has declared that United Nations Ambassador U Kyaw Moe Tun is the only person authorised to represent the country in The Hague.

However, for the generals, defending the country against the genocide accusation is largely a means to an end: they will use this opportunity to conduct themselves as the legitimate representatives of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar on a global stage. One should not fall for this trick, or not again: Already in April 2021 the military managed the feat that a general participated in an online-event of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), thereby bypassing the UN Secretary General’s own advice not to cooperate with the junta.

The ICJ is one of the principal legal organs for investigating violations of the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, to which Myanmar is a signatory. To invite the junta to represent the country means to offer them the chance to use the court as a platform for strategic litigation where no longer the crime, but the performance of legitimacy will be key: When the ICJ reopens the case against Myanmar, the Rohingya genocide is not a primary concern of the generals. Rather, it is to be ‘Myanmar’. The ICJ has a historical opportunity to avoid such an ethical, political and legal failure.

Read the full post at Allegra Lab.

Myanmar 10 Monate nach dem Putsch und die Situation der Rohingya – für ARD alpha

Mit Tilman Seiler habe ich mich nun schon zum zweiten Mal über die Widerstandsbewegung in Myanmar unterhalten, die sich nach dem Militärputsch vom 1. Februar 2021 im ganzen Land gebildet hat. Er fragte, wie erfolgreich diese sei, wie fest im Sattel die “Putschregierung” sitzen würde und auch, was von der Ankündigung des Militärs zu halten sei, es werde Neuwahlen geben nachdem Min Aung Hlaing die im November 2020 stattgefundenen Parlamentswahlen für ungültig erklärt hatte. Meine Prognosen sind realistisch, also recht düster.

Ein zweites Thema betraf die Situation der Rohingya im weltgrößten Flüchtlingscamp in Bangladesh. Hier wollte Herr Seiler wissen, wie die Regierung des angrenzenden Nachbarstaats mit den Geflüchteten umgehen würde und auch, was die internationale Weltgemeinschaft tun könne, um die mittlerweile 1,5 Millionen Rohingya zu unterstützen. Ich berichtete von den laufenden Plänen Bangladeshs, circa 100.000 Rohingya auf die eine vorgelagerte künstliche Insel in der Bengalischen See zu verlagern und sagte auch, dass dies im großen Fall gegen den Willen der Menschen dort geschehe.

Darüber hinaus erinnerte ich daran, dass vor allem im Fall staatenloser Geflüchteter wir “bei uns vor der Haustür” mit der Unterstützung beginnen können, nämlich indem man das eigene Asylsystem reformiert, welches bei Staatenlosen in den meisten Fällen immer noch unzureichend greift: Menschen, die keine offiziellen Dokumente zu ihrer Identifikation vorweisen können, haben es hier besonders schwer.

Das zehnminütige Gespräch ist in der ARD alpha-Mediathek zu finden.