Our collaborative article “Exiled Activists from Myanmar: Predicaments and Possibilities of Human Rights Activism from Abroad“, published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice (Oxford University Press), is finally out! 🎉

I am very proud of the work that my colleague Samia Akhter-Khan, my two Ph.D. students Sarah Riebel and Nickey Diamond, another author from Myanmar (who has to use a pseudonym for reasons of safety), as well as myself have managed to achieve under very difficult circumstances.

This article was born out of necessity to engage with the topic of exile. None of us had ever wanted to study yet alone experience this existential state of being. The empirical material we draw on in this article stems from autoethnographic accounts (Nickey Diamond and Demo Lulin), semi-structured interviews and conversations with around forty exiled activists currently residing in Thailand, the US, the UK, Austria, and Switzerland (Samia Akhter-Khan and myself) as well as extensive ethnographic work with exiled activists in Thailand (Sarah Riebel).

In this article, we put forward the concept of the ‘exiled activist’ to highlight the predicaments and the possibilities that practicing human rights activism from abroad bring with it. From our analysis, we have developed three so-called ‘practitioner points’ that might guide INGOs, NGOs, states and other bodies to properly relate to exiled activists from Myanmar. These are:

1. Develop trauma-informed support systems for exiled activists by integrating psychosocial care and peer-based mental health resources into human rights programming and diaspora organizing.

2. Adapt partnership models to accommodate the shifting positionality of exiled activists, recognizing their need for secure digital platforms, flexible funding, and shared decision-making across borders.

3. Acknowledge and navigate political divisions within diverse groups of exiled activists – such as differing views on the National League for Democracy, the military, or the Rohingya – by avoiding assumptions of unity and instead fostering inclusive collaboration that respects diverse activist trajectories and lived experiences.

We have made our article openaccess so that everyone is able to download it. Currently, we are working on a shorter version in Burmese/Myanma, to also allow those who do not speak English to read about this important topic.

Thank you to all exiled activists who have participated in this study, trusted us and shared their stories – and to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the support of scholars at risk over the last years!

Category Archives: field research

Open Acess: “Asylum Interviews in the UK”. Published in Social Anthropology

My new article “Asylum Interviews in the UK. The problem of evidence and the possibility of applied anthropology” has just been published with Social Anthropology / Anthropologie Sociale (33/3: 51-65).

In this article, I interrogate the process how evidence is established in asylum procedure by engaging with anthropological and socio-legal literature on evidence and credibility assessments. Drawing on ethnomethodology, I analyse asylum interviews and show in what ways evidence can be understood as the result of an asymmetrical co-construction. As a result of this procedure, the individual applicant disappears and a ‘case’ is established.

Anthropologists who write country of origin reports based on such ‘case material’ for tribunals and courts can highlight the asymmetries in evidence-making and question the very categorisations through which the state operates. The article contributes to ongoing debates on the role of anthropologists and their knowledge as experts in court.

It is open access and can be downloaded here.

Seeing beauty in details

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the Palm of Your Hand

And Eternity in an Hour.

(William Blake. Auguries of Innocence, 1803/1863)

“We are all stuck” – On (not) failing our students

We are way into the winter term in all public universities in France. I am currently on a research sabbatical at the University Paris-Nanterre where I also teach a course on the Introduction to Legal Anthropology.

Half an hour before my lecture is about to start, one student already sits prepared with their laptop in the hallway. I open the door to the lecture room to allow them to sit more comfortably. But it is as freezing in the room as it is in the hallway. There is no heating in the building. I wonder how many of my students might come today given the heavy rainfall …

Ten minutes before my lecture, I check my emails. I see that several students have written to me already. Only one calls in sick, all others are stuck in the outbound RER A train from central Paris to Nanterre. There has been an incident, the students explained: “We are all stuck”. Another one shares a screenshot of the offical traffic announcement and an additional photograph: an official attestation that there has been a disruption. The document carries the title “Attestation de pertubation”

The date and time is neatly printed and I contemplate how fast and effective not being fast and effective can be. I suggest to the student later to use this textual artefact as an entry point to an essay my students are supposed to write at the end of the term on the everyday life of the law.

It is 10.30h and I decide to see who might have shown up despite the rain falling and the train being late. The room is half full already and within the next 20 minutes the rest trickle in. We are almost at full capacity and I am seriously impressed.

It is on the same day that I learn that in France there is no longer an obligation to attend classes in presence if your personal circumstances do not allow you to do so. Students may study long distance at all universities in France for health-related reasons or because they have to work. At the end of my course I will have to grade essays of students whom I will have never seen in person and who will not have attended a single lecture of mine on campus.

I wonder: what kind of anthropologists are we releasing into the world if the only encounter many students have with the discipline is via self-study ? No dialogue with teachers, no spending time with classmates, no campus experience. Not only that the state keeps on moving the universities beyond the bande péripherique into suburbia, by allowing students to study long-distance, it reduces the campus to mere sites of administration. In the name of “flexibility”, students work towards their grades, but are being deprived of what Bell Hooks has called “the most radical space of possibility in the academy”: the classroom.

Universities are easier to manage if fewer people are around. One might be tempted to reframe long-distance studies as “needs-centred”. Paris already suffered from high living costs before the Covid-19 lockdowns struck. After 2021, many never moved back to the city, but remained in their home towns far away. At times, the campus feels deserted – a striking difference to 2018 and 2019 when I last spent some time in Paris on fellowships.

The students who do attend my seminar, always listen attentively and eagerly write down what I am presenting on my slides. I have split the seminar into two parts: the first is a lecture, the second was intended as an interactive space for discussing the weekly reading and give them the possibility to ask questions – in French or English. However, only very few attend the second part of the seminar. I now understand that this is the case because very few have read the text. I was warned by other lecturers that this is indeed the case: “Students do not read texts.” When I inquired why, the answer was always because they are overworked – from having to take too many courses and from having to work in order to finance their studies …

But anthropology is not a subject that can be taught only. It needs to be ingested until it has become part of oneself. Students need to anthropologize themselves throughout their studies in order to be able to later claim “I am an anthropologist” and mean themselves instead of a mere profession. Anthropology needs to become an integral part of one’s own humaneness, ideally, before one can collaborate with others and analyse what one has learned from them in an ethical manner. But the discipline is increasingly expected to be taught in ways that ensure it remains outside of our students’ individual experience.

Our most important task is therefore to get students back into the classroom while at the same time opening that very classroom up to the world. Rather than transmitting a particular kind of ‘knowledge’, we should be transmitting that anthropology provides a multitude of ways of seeing and conceptualizing humanity as such. While taking our students and their current experiences seriously, our task is also to de-self-center their existing worldview and help them get unstuck. We do not need more ‘attestations des pertubations‘, we need ‘pertubations des attestions‘!”

La Flâneuse

Flâneuse [flanne-euhze], nom, du français. Forme féminine de flâneur [flanne-euhr], un oisif, un observateur flânant, que l’on trouve généralement dans les villes.

An incremental part of anthropology has always been photography for me. It can be used as an aide mémoire to simply remember where one has been or whom one has encountered on a particular day, thus substituting for fieldnotes. It can also be used as a methodological tool in order to detect the ‘minor modes’ in everyday life or in co-existence. A photograph can be scrutinized for its details, revealing more and more of them, every time one looks closer. But photography can also help express oneself when words fail. Rather than serving the eye, it serves the mouth that does not find the right words or ceases to speak alltogether. When used in this way, photography is neither only a method nor a product. It becomes a mode of existence in itself.

Femme vidant le canal

Une petite fille qui n’a aucun souvenir de la guerre exhorte les Français à s’en souvenir

14 millions de livres enfermés dans quatre tours pendant que les chercheurs travaillent sous terre

Partie d’une peinture murale de la faculté d’anthropologie de l’Université Paris-Nanterre, réalisée par un artiste déterminé.

Le Génie de la Liberté au sommet d’un arbre — illusions d’optique à la Place de la Bastille

Research Colloquium at Université Paris-Nanterre

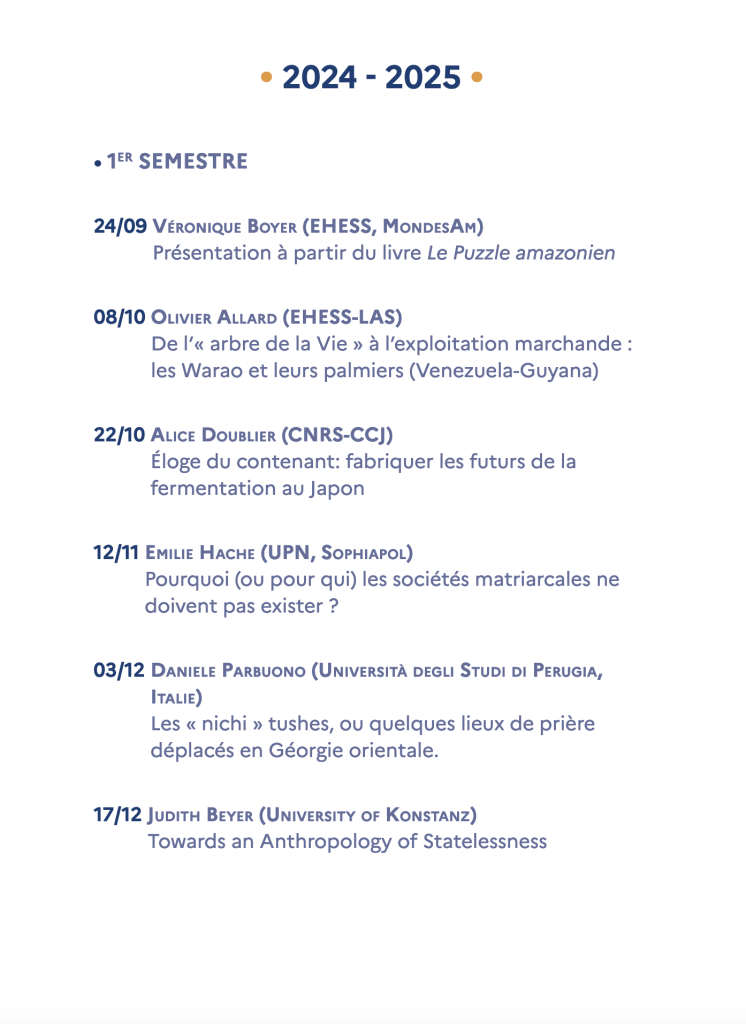

This winter term, I will be spending some time with my anthropology colleagues at Paris-Nanterre as part of the Laboratoire d’Ethnologie et de Sociologie comparative (LESC), part of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS).

One part of my research stay is devoted to working on my current project: “Towards an anthropology of statelessness”. I will be speaking at the Department’s Colloquium in December (see plan below). I will also be teaching a course in legal anthropology … more about this one later.

The colloquium is free and open to the public, everyone is welcome.

In honour of Akbar Hussain (1944 – 2024)

On July 28, 2024 at 4.30pm, my dear Akbar Hussain passed away.

We have known each other for over a decade and as is the case with many central interlocutors in anthropology, there is never a way to thank them enough for what they are enabling us to achieve. Akbar Hussain was born as Mohammad Akbar Hussain Khan. He descended from a well-known Turkic Qizilbash family of high-ranking warriors, originating from Lankaran in what is now Azerbaijan. His ancestors had fought in the British Army and their heroic services were rewarded with name titles – such as “Captain” – and with land titles – such as a grant given to Akbar Hussain’s great-grandfather in 1886 that allowed him to relocate from the Northern part of British India to Burma. While the family raised their children in Myanmar, they continued to go back and forth to countries in the East such as Pakistan (since 1947) and the West (Akbar Hussain himself lived in the USA for many years). Theirs was a polyglott Muslim family as most Muslim families are in Myanmar. In contrast to his ancestors, however, Akbar Hussain did not serve any army; he served his mosque in downtown Yangon. He knew its history better than most, and due to the location of his appartment, he also knew its present: who would go in and out, at what time and for what purpose. He was curious enough to engage with my curiosity, multi-lingual so that we could easily communicate about the most complicated matters, very knowledgable and yet modest and able to admit when he did not know something – suggesting that I probe literature instead of his brain.

This is a very blurry picture of the two of us, but somehow, it says so much about our relation. Akbar Hussain was always there when I needed him and even, when I did not know that I needed him. He always kept to the background or to the sidelines, observing everything, commenting quietly afterwards or hinting at things, pointing at people, alerting me what to pay attention to, and whom to listen to more closely. Translating from Urdu to English for me at times, and always making sure that I get home safely at night after a procession or another long day spent at his house with him and his lovely wife.

This is a very blurry picture of the two of us, but somehow, it says so much about our relation. Akbar Hussain was always there when I needed him and even, when I did not know that I needed him. He always kept to the background or to the sidelines, observing everything, commenting quietly afterwards or hinting at things, pointing at people, alerting me what to pay attention to, and whom to listen to more closely. Translating from Urdu to English for me at times, and always making sure that I get home safely at night after a procession or another long day spent at his house with him and his lovely wife.

He passed away and I could not say goodbye properly, neither in person, nor at the graveyard. He had asked me many times to come see him during the last few years. We communicated via a third person who would scan his handwritten letters to me in an internet café … as if it were the 1990s, as if there was a military dicatorship in place … wait … oh. And I would write self-censored emails back, because I knew that I was sending them to an address and a person whom I did not know and that I relied on that person to print them out and give them to him when he came to pick up his ‘mail’. So he knew all about my private life in safe Europe, but little of my fears and worries for him, his wife and everyone in Myanmar, really, as there was no way to ask how he was really doing in the current situation. He never spoke of politics, he sticked to writing about his health, his religion, the weather and of course reported meticuously about all upcoming festivities at the mosque.

We met at the mosque over 10 years ago and soon I realized that he frequently stayed at the managing trustee’s house at the time. He was his right hand, but also a careful observer as the person was very old and also not uncomplicated, feared by some even. Akbar Hussain knew how to handle complicated people, he even knew how to deal with a female German anthropologist who intruded into the daily life of the mosque, too, but – in contrast to tourists or journalists who dropped in and out, sometimes coming only for one day in the year – Ashura – to witness, record and distribute gruesome images of men flagellating themselves or walking over burning coal – to then disappear again, thinking they had understood something, he dealt with me as someone who would always come back and stay because I somehow never understood enough. And he kept explaining. Eventually, when he thought, I had acquired enough knowledge, he asked me: “Hey, when will you become Shia?” In my book, I recall this sentence and have interpreted it in the following way:

‘Hey, when will you become Shia?’ he often asked, which indicated to me that it would have been easier for him to conceive of me as a converted ‘member’ than as someone who was simply very interested (and increasingly knowledgeable) in what it means to be a Shia in Yangon. My interest and knowledge in the Shia religion were fine, but they were not what mattered in the end: membership in the community did (Beyer 2024 ,8)

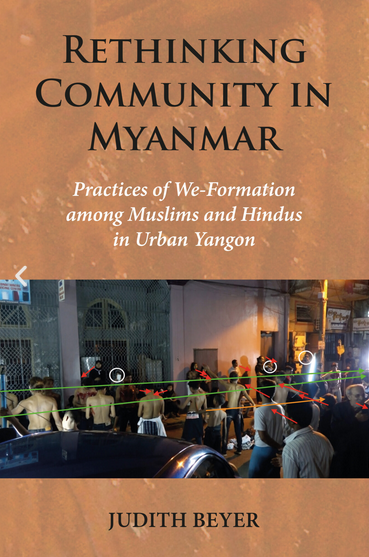

He is on the cover photograph of my Myanmar book, as usual at the sidelines, with his back even turned away from where supposedly the ‘action’ is, yet later able to deconstruct and interpret the event with me in all its details. Since we often sticked together, everyone initiatially wondered who I was. The following conversation is from a transcript I made between Akbar Hussain, me and another person from the mosque who explained to me how Akbar Hussain would answer this question in my absence.

He is on the cover photograph of my Myanmar book, as usual at the sidelines, with his back even turned away from where supposedly the ‘action’ is, yet later able to deconstruct and interpret the event with me in all its details. Since we often sticked together, everyone initiatially wondered who I was. The following conversation is from a transcript I made between Akbar Hussain, me and another person from the mosque who explained to me how Akbar Hussain would answer this question in my absence.

Third person (to me): they all ask ‘where is she from, where is she from?’ Akbar Hussain then always says ‘my relation’ #00:08:44-6#

AH Because my relation are all foreigners #00:08:49-8#

J That is true #00:08:51-8#

AH So they thought that you are my relative #00:08:57-3#

J That’s good – we can keep it this way (laughs) #00:09:02-9#

AH They ask me ‘from America?’ ‘No, I say, from Germany.’ They are very inquisitive (laughs) #00:09:18-7#

J That’s fine, I am also inquisitive #00:09:23-9#

(all laughing) #00:09:26-6#

All his relatives are foreigners, he said, because Akbar Hussain had chosen to never give up his Pakistani citizenship. He loved Myanmar and Yangon, the downtown area, his street and the mosque, but his home was in Pakistan where he spent his youth and went to university. He was fiercely political, one of the harshest critics of the mullahs in Pakistan and in Afghanistan, of those who perverted his beloved religion and his culture. He was proud and knowledgable and sometimes so outspoken that when he picked up the microphone at the mosque to condemn the killing of innocents, the endemic corruption or anything else going on in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Iran or Northern Africa, one could mistake him for being radical himself. He was radical in the sense that he did not only believe, but stood up for what he believed. But this concerned politics and religion abroad. He was careful to not position himself publicly when it came to Myanmar – knowing that he was a foreigner by choice. Someone who had to frequent the downtown visa section of the Ministry of Foreign affairs every few months to renew his residence status. While he had tried to incorporate me into his ‘community’ and even his family, he himself had remained Other all the time … we both occupied the same positionality, I later understood.

I read about Akbar Hussain’s death on the Facebook page of a friend of mine from Yangon. She is the wife of the late managing trustee and knew Akbar Hussain very well. He saw her getting married at a young age, he saw her two children growing up, he went in and out of her house in downtown for many years and he supported her late husband in many ways. She is thankful for him, her story being one of the numerous stories that need to be told because they are paradigmatic for Myanmar’s Muslims: for the way religious divides are being bridged, for the way religious tolerance is being practiced at a low level, for the way in which the people of Myanmar are capable of transcending the categories that have been imposed upon them throughout colonial history. These are the stories we do not get to hear about too much, but they exist and they matter. Just like the people that tell them.

Akbar Hussain, may you rest in peace and … thank you.

မိသားစုနဲ့ထပ်တူအလွန်တရာမှဝမ်းနည်းကြေကွဲမိပါတယ်စိတ်မကောင်းလိုက်တာသူသိတ်ချစ်မြတ်နိုးလှတဲ့လလေး Muharram လမှာဆုံးသွားရှာရတာစိတ်ထိခိုက်ဝမ်းနည်းမိပါတယ်

Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji’un إِنَّا لِلَّٰهِ وَإِنَّا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعُونَ.

Come work with me! PhD positions on Europe

If you are a recent graduate (MA-/MPhil-degree holder) with an interest in pursuing a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology under my supervision, please consider applying for a PhD position at the newly established Graduate School “Post-Euroentric Europe. Narratives of a World-Province in Transformation” at the University of Konstanz.

Together with 10 other professors we have worked hard in the last years to realize an ambitious and highly relevant programme that is aimed at decentring and questioning narratives about Europe.

“Where is Europe?” we might be tempted to ask. “And is it even one place?” (Attali 1994). Is Europe to be found in the minds and hearts of the refugees detained in camps on its southern border, for whom it is place of longing, even as it denies them entry or sets up hurdles in their way? How and to what extent do “soft” cultural factors in the form of collective narratives and imaginations solidify into “hard” institutional realities, which in turn have a reflexive effect on the availability of narrative resources?

While it has long been customary to regard “Europe” and “modernity” as more or less synonymous, only recently has there been a systematic examination of the fact that the European continent was and is permeated by political-cultural demarcations and asyn-chronicities, even within its own borders. Increased attention to non-European traditions or those marginalized in Europe’s dominant self-narrative not only guides a redefinition of Europe’s position in world affairs; it also requires us to diversify notions of Europe from within.

The work of our graduate program aims to contribute to the historical and contemporary demonopolization of the concept of Europe in local contexts, which has been tightly restricted to dominant traditions in the West-Central European area.

Within this interdisciplinary Graduate School, I am particularly interested in supervising anthropological PhD projects with a focus on statelessness in Europe or its border regions or on one of the various European independence movements (e.g. in Catalonia, Bretagne, Basque Country, Scotland, Celtic Nationalism, One Tirol, … ). Other topics are possible, too, as long as they fit the programme and are based on ethnographic field research and lie within the field of political and legal anthropology.

Make sure you read the entire research programme carefully before preparing your application! If you have questions, contact me under my uni-konstanz email-address.The deadline is already 30 June 2024!

Book Launch: Rethinking Community in Myanmar. 15th Int. Burma Studies Conference

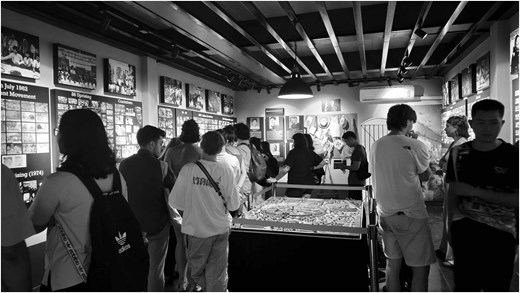

At the 15th International Burma Studies Conference, hosted at the University of Zurich, (9-11 June 2023), I launched my book Rethinking Community in Myanmar. Practices of We-Formation Among Muslims and Hindus in Urban Yangon.

Informal book launch in good company — while missing many from Myanmar

I wanted to celebrate the publication of my monograph: 10 years in the making if I count from the first days of fieldwork in 2012-2013. Good anthropological monographs take time and they are never the result of one indiviual only, even though writing can be a solitary process, particularly towards the end. I wanted to use the occasion of having over 200 Myanmar specialists gathering in one place, to say “Thank you” publicly to all the important people who could not be present in Zurich, but also to those who were able to share a glass of wine with me that day.

I set out by thanking my Muslim and Hindu interlocutors in Myanmar — there can neither be an anthropology nor an ethnography without the people ‘in’ (paraphrasing Tim Ingold). I owe them everything and I am glad that there will be an open access version of my book coming out towards the end of this year that will allow at least some of my interlocutors to download the book in Myanmar — I cannot bring it to them at the moment; not so much because it would be dangerous for me (it might be), but because I simply cannot take the risk of putting them into danger once I have left the country or their houses …

I then thanked my four research assistants — my KRA (Kachin Research Army) — and I explained to the audience of Burma/Myanmar experts that I profited enormously from them having conversations with my interlocutors about what it means to be a member of a minority in a majority Buddhist country. Listening in — as I am currently developing also in another context — is a methodologically fruitful approach to conduct fieldwork or carry out digital ethnography where fieldwork is not possible, because it decenters the anthropologist. What I am interested in mostly is “free-flowing talk” where my interlocutors do not try to guess what it is I want from them (in terms of what they might be expected to tell me), but where I can simply follow them having conversations with one another. Since all of my research assistants were Christian Kachin women, it was not religion they shared with my interlocutors (who were Muslims and Hindus), but the experience of being ‘slotted in’ as members of ‘communities’.

I also thanked my colleagues in Myanmar who had been professors of Anthropology at the University of Yangon prior to the attempted military coup in February 2021. Thanks to them, my PhD students received research visa, thanks to them, I had the opportunity of teaching and learning from young anthropology students, and thanks to them I learned a lot about the history of the discipline in Myanmar and about the history of the University of Yangon. I truly hope that one day they will be able to return to their professional jobs — which they cherished a lot, and to their students whom they loved.

None of these people could be with my family, my PhD students, and the other Myanmar scholars that day.

Thanking those who were there

I was happy to be surrounded by many friends, who had helped in different ways to bring this book to fruition: many of my colleagues had read draft chapters, some had written reviews or are going to write them. Alicia Turner gave some introductory words — she knows the book very well as she has written the most constructive and helpful review that made the final product so much better!

The managing editor of NIAS Press, Gerald Jackson, had come from Copenhagen to Zurich with his research assistant Julia Heinle and with a lot of amazing books on Southeast Asia and on Myanmar in tow. He took my book project on board and steered it smoothly through the production process in not even two years from the submission date!

My PhD students who are working on Myanmar, were all present, too. We discussed my material just as much as we discussed theirs. They all completed long-term ethnographic fieldwork in or on Myanmar and I can’t wait to see their own books!

And — last but not least — my family — who accompanied me from 2012 onwards and carried out their own research projects in Yangon: on the politics of cultural heritage in one case and on what it means to go to a local school in Chinatown in Yangon in the other case.

Thank you to everyone who was there that evening — be it in spirit or in the flesh — I am very grateful for the support I have received in the last decade. I hope the book will be useful to many.

We-formation. Reflections on methodology, the military coup attempt and how to engage with Myanmar today. Lecture in Paris, 16 May 2023

In this invited lecture, I will discuss my concept of “we-formation” in regard to three different topics: First, as anthropological theory and methodology; Second, as a way to make sense of the resistance against the attempted military coup and third in regard to the possibility of a public anthropology of cooperation in these trying times.

First, I will explore the concept in regard to its theoretical and methodological innovativeness, taking an example from my Yangon ethnography as illustration. We-formation, I argue in my book Rethinking community in Myanmar. Practices of we-formation among Muslims and Hindus in urban Yangon, “springs from an individual’s pre-reflexive self-consciousness whereby the self is not (yet) taken as an intentional object” (8). The concept encompasses individual and intersubjective routines that can easily be overlooked” (20), as welll as more spectacular forms of intercorporeal co-existence and tacit cooperation.

By focusing on individuals and their bodily practices and experiences, as well as on discourses that do not explicitly invoke community but still centre around a we, we-formation sensitizes us to how a sense of we can emerge (Beyer 2023: 20).

Second, I will put my theoretical and methodological analysis of we-formation to work and offer an interpretation of why exactly the attempted military coup of 1 February 2021 is likely to fail (given that the so-called ‘international community’ does not continue making the situation worse). In the conclusion of my book I argue that the “generals’ illegal power grab has not only ended two decades of quasi-democratic rule, it has also united the population in novel ways. As an unintended consequence, it has opened up possibilities of we-formation and enabled new debates about the meaning of community beyond ethno-religious identity” (250).

Third, I will discuss how (not) to cooperate with Myanmar today. Focusing on what is already happening within the country and amongst Burmese activists in exile, but also what researchers of Myanmar from the Global North can do within their own countries of origin to make sure the resistance does not lose momentum. In this third aspect, I take we-formation out of its intercorporeal and pre-reflexive context in which I came to develop the concept during my fieldwork in Yangon and employ it to stress a type of informed anthropological action that, however, does not rely on having a common enemy or on gathering in a new form of ‘community’ that has become reflexive of itself. Rather, it aims at encouraging everyone to think of one’s own indidivual strengths, capabilities and possibilities and put them to work to support those fighting for a free Myanmar.

You can purchase my book on the publisher’s website: NIAS Press.

Here’s the full programme of the Groupe Recherche Birmanie for the spring term 2023: