Our collaborative article “Exiled Activists from Myanmar: Predicaments and Possibilities of Human Rights Activism from Abroad“, published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice (Oxford University Press), is finally out! 🎉

I am very proud of the work that my colleague Samia Akhter-Khan, my two Ph.D. students Sarah Riebel and Nickey Diamond, another author from Myanmar (who has to use a pseudonym for reasons of safety), as well as myself have managed to achieve under very difficult circumstances.

This article was born out of necessity to engage with the topic of exile. None of us had ever wanted to study yet alone experience this existential state of being. The empirical material we draw on in this article stems from autoethnographic accounts (Nickey Diamond and Demo Lulin), semi-structured interviews and conversations with around forty exiled activists currently residing in Thailand, the US, the UK, Austria, and Switzerland (Samia Akhter-Khan and myself) as well as extensive ethnographic work with exiled activists in Thailand (Sarah Riebel).

In this article, we put forward the concept of the ‘exiled activist’ to highlight the predicaments and the possibilities that practicing human rights activism from abroad bring with it. From our analysis, we have developed three so-called ‘practitioner points’ that might guide INGOs, NGOs, states and other bodies to properly relate to exiled activists from Myanmar. These are:

1. Develop trauma-informed support systems for exiled activists by integrating psychosocial care and peer-based mental health resources into human rights programming and diaspora organizing.

2. Adapt partnership models to accommodate the shifting positionality of exiled activists, recognizing their need for secure digital platforms, flexible funding, and shared decision-making across borders.

3. Acknowledge and navigate political divisions within diverse groups of exiled activists – such as differing views on the National League for Democracy, the military, or the Rohingya – by avoiding assumptions of unity and instead fostering inclusive collaboration that respects diverse activist trajectories and lived experiences.

We have made our article openaccess so that everyone is able to download it. Currently, we are working on a shorter version in Burmese/Myanma, to also allow those who do not speak English to read about this important topic.

Thank you to all exiled activists who have participated in this study, trusted us and shared their stories – and to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the support of scholars at risk over the last years!

Category Archives: existentialism

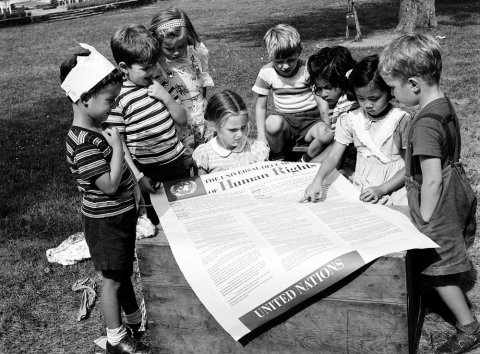

Crimes against commonality

Before all other forms of membership, we are “all members of the human family”, as the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has specified. Thus, the international legal concept of crimes against humanity is crucial because all war crimes are predicated on the fact that those committing these atrocities are enabled once they succeed in establishing difference that makes us forget our human commonality.

We cannot but make do with what the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has called the imaginary order – the way in which we try to relate to others by looking for similarities and differences, mainly in order to acknowledge ourselves. We need the ‘other‘ to sustain ourselves as the I(ndividual) we imagine ourselves to be.

The imaginary order is the order of world-making in the sense of Hannah Arendt (1959) for whom the world is not ‘out there‘, but rather that which arises between people in discourse, as I will develop in an upcoming presentation. We have to keep engaging with others, irrespective of the fact that we will never really understand each other entirely. But we are obliged to keep trying. There is no other way.

“For the world is not humane just because it is made by human beings, and it does not become humane just because the human voice sounds in it, but only when it has become the object of discourse … We humanize what is going on in the world and in ourselves only by speaking of it, and in the course of speaking of it, we learn to be human” (Hannah Arendt, 1959, 24-25)

Human commonality is already there from the beginning, transcending all dichotomies, whereas difference is something we can only ever bring about consciously. What we have in common and what makes us human is that we are split by language, as Lacan argued. If we acknowledge this, we might be able to include the other not as an opposite ‘they’ but as part of our own unconscious: we are always other to ourselves first.

Boat is a man

2024 has been the deadliest year for migrants trying to cross the Channel in small boats to reach the UK, with 69 deaths reported (Refugee Council 2025). British politicians have been referring to the circumstances under which people migrate to the UK as “the small boat crisis“ and subsequently made a “small boat deal“ with countries such as Ruanda, to which they wanted to ship people to.

Before the Labour party came to power, they accused the Tories of “having lost control of small boat migration“. Now, that they are in power, they claim that there is “no nice or easy way of doing it“. Getting rid of people who came by boat…

But what if boat were a man?

I recently bought a small booklet filled with Walter Benjamin’s short stories. Tales out of loneliness is its subtitle. In it, there is a 1-page story entitled How the Boat was Invented and Why It Is Called ‘Boat‘. It follows a similar pattern as Benjamin’s short story on Why the elephant is called ‘elephant‘ that immediately precedes the story about the boat.

Here’s how Boat’s story goes:

Before all the other people, there lived one person and he was called Boat. He was the first person, as before him there was only an angel who transformed himself into a person, but that is another story.

So the man called Boat wanted to go on the water — you should know that back then there was a lot more water than today. He tied himself to some planks with ropes, a long plank along the belly, that was the keel. And he took a pointed cap of planks, which was, when he lay in the water, at the front — that was the prow. And he stretched out a leg behind him and navigated with it.

In this manner he lay on the water and navigated and rowed with his arms and moved very easily through the water with his plank cap, because it was pointed. Yes, that is how it was: the man Boat, the first man, made himself into a boat, with which one could travel on water.

And therefore — of course that is quite obvious — because he himself was called Boat, he named what he had made ‘boat‘. And that is why the boat is called ‘boat‘.

(Walter Benjamin, 26 September 1933; published posthumously)

The “small boats crisis” is Boat’s crisis, the crisis of man. This is the elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about. Because they do not know why the elephant is called ‘elephant‘ either.

Philosophy saves lives.

Decaying is still living

Lacan auf der Spur

In seiner hommage an Jacques Lacan anlässlich der Erstveröffentlichung von Seminar XV, L’Acte psychanalytique, sagte Jacques-Alain Miller folgendes:

‘Moi, la vérité, je parle’ … In dieser Eigenschaft lehrt Lacan. Sich verständlich zu machen ist nicht lehren, sondern das Gegenteil. Man versteht nur das, was man bereits zu wissen glaubt. Genauer gesagt, man versteht immer nur einen Sinn, dessen Befriedigung man bereits erfahren hat. Das bedeutet, dass man immer nur seine Phantasien versteht. Und man wird nie belehrt, außer durch das, was man nicht versteht.[1] (Jacques-Alain Miller 2024, min. 1:19:12)

Der Satz Moi, la vérité, je parle! („Ich, die Wahrheit, spreche“) ist aus einem Vortrag Lacans entnommen, den dieser im November 1955 in Wien an der Neuropsychiatrischen Universitätsklinik gehalten hatte.[2] Und es ist dieser Vortrag, auf den sich Lacan am Ende des 9. Kapitels des Seminars X bezieht:

Es ist Diana, die ich als die Flucht (fuite) oder die Fortsetzung (suite) dieses Dings (Chose) zeigend bezeichne. Das Freud’sche Ding ist das, was Freud hat fallen lassen – aber es macht weiter nach seinem Tod, und es reißt noch die ganze Jagd mit sich, in der Gestalt von uns allen. Diese Verfolgung, wir werden sie das nächste Mal weiterführen“ (Lacan 2010: 164).

Dieses Seminarende, so gesprochen am 23. Januar 1963, ähnelt dem Sitzungsende am 19. Dezember 1962. Da sagt Lacan:

… es gibt die Jagd Dianas, über die ich Ihnen zu dem von mir gewählten Zeitpunkt, dem Zeitpunkt der Hundertjahrfeier von Freud, gesagt habe, dass sie das Ding (Chose) der Freud’schen Suche war. (Lacan 2010: 108)

Was ist „das Ding der Freud’schen Suche“, auf das sich Lacan in Seminar X bezieht? [3] Und was hat es mit der „Jagd Dianas“ auf sich?

Diana und Actaeon

Diana („die Leuchtende“) ist die römische Göttin der Jagd, der Natur, und die Schutzherrin der Frauen und Kinder. In der mythischen Erzählung von Ovid wird sie als „hochgegürtet“ und „jungfräulich“ beschrieben. Sie badet mit ihren Nymphen in einer Quelle in einer Grotte inmitten des Waldes, ihre Waffen und Kleider abgelegt, als Actaeon, der Enkel des Kadmos, Gründer und König von Theben, in ihren Wald eintritt. Er trifft in der Grotte auf die Göttin und sieht sie ohne Kleider. Die erboste Göttin bespritzt ihn mit Quellwasser und verkündet „Nun darfst du gern erzählen, du habest mich ohne Kleid gesehen, wenn du es noch wirst erzählen können!“ Sie lässt Actaeon ein Hirschgeweih wachsen, spitzt seine Ohren zu, gibt ihm Hufe und „auch noch die Angst“ (lat. pavor). Actaeon ergreift in dem Moment die Flucht, in dem er sein Spiegelbild sieht. Ovid schreibt allwissend: „[s]obald er aber Gesicht und Geweih im Wasser gesehen hatte, wollte er „Ich Elender!“ sagen – aber keine Stimme folgte! … nur sein früheres Bewusstsein blieb erhalten.“ Actaeon wird sodann im Wald von seinen eigenen Hunden gewittert, die ihn nicht mehr erkennen, ihn verfolgen und letztendlich reißen. Erst dann war der Zorn der Göttin Diana gesättigt, so Ovid.

Die Hundertjahrfeier, die Lacan im Zusammenhang mit der „Jagd Dianas“ anführt, war jene zu Ehren von Sigmund Freuds 100. Geburtstag in Wien. Im daraus entstandenen Vortragstext, findet sich eine Stelle, in der Lacan seine Zuhörer als „Spürhunde“ bezeichnet (Lacan 2019a: 484), sowie einen sehr langen Absatz, in dem er zunächst Freud als Actaeon darstellt, der sich „fortwährend durch von Anbeginn auf die falsche Spur gesetzte Hunde losgelassen, bis zur Verbissenheit darum bemüht, dass sie seine Verfolgung wieder aufnehmen, ohne den Lauf zu [sic!] verlangsamen zu können, worin allein seine Leidenschaft für die Göttin ihn führt. Ihn so weit führt, dass er erst in den Grotten anzuhalten vermag…“ (485). Lacan bezieht sich meines Erachtens hier auf all das, was vor Actaeons Verwandlung in einen Hirsch geschehen ist – das, was ihn überhaupt vor die Göttin hat treten lassen. Nach Ovid ist Actaeon in dem ihm „unbekannten“ Wald „herumgeirrt“, seine Schritte seien „unsicher“ gewesen und es sei „das Schicksal“ gewesen, dass ihn in die Grotte geführt habe. So wie ich Lacan lese, schreibt er Actaeons Eintritt in die Grotte dessen Begehren zu. Das Begehren ist nichts, was man verstehen könnte, nichts, zu dem ein Subjekt unmittelbaren Zugang hätte.[4] Es ist vielmehr etwas, das einen sich unsicher fühlen und herumirren lässt. Aber es ist auch das, was in Richtung Wahrheit zieht. Und so führt Lacan in seinem Wiener Vortrag weiter aus, die Grotte Dianas sei „für seine [Freuds] Schüler noch weit davon entfernt erreicht zu werden, sofern sie sich nicht gar weigern, ihm dorthin zu folgen, und damit ist der Aktäon, der hier in Stücke gerissen wird, nicht Freud, sondern sehr wohl im Maße der Leidenschaft, die ihn entflammte … jeder Analytiker“ (Lacan 2019a: 485). Der Vortrag Lacans in Wien ist somit auch eine Abrechnung mit der Wiener Psychoanalyse nach Freud, weil Lacan der Ansicht war, dass man von dieser Jagd abgelassen habe.[5]

Wahrheit, Begehren und die Angst

Wenn Lacan sagt Moi, la vérité, je parle, dann ist nicht er der Wahrheitsverkünder, genauso wenig wie Freud es war, sondern es geht ihm darum, die anderen „Hunde, zu denen Sie werden, wenn Sie mich vernehmen…“ (484) auf ihren Weg in die Grotte anzuleiten, näher heran an den Ort an dem die Wahrheit „von/für sich“ spricht“ (481).[6] Lacan möchte, dass man wie Actaeon seinem Begehren nicht nachgibt, dass man wie jemand ist, der nicht weiß, was ihn antreibt, der aber Freud und Lacan hörend und lesend, sich auf den eigenen Weg macht.

Doch was passiert in dem Moment, wo Actaeon auf die Göttin trifft? Er bekommt von Diana als Strafe die Sprache weggenommen und sie gibt ihm die Angst. Im Deutschen sagt man „es verschlägt einem vor Angst die Sprache“ und so ist es bei Actaeon tatsächlich. „Auf welche Distanz muss ich die Angst halten, um zu Ihnen darüber zu sprechen …?“ fragt Lacan daher in Seminar X. Dies sei „seit Beginn“ seine Frage gewesen. Angst ist ein Affekt (Lacan 2010: 24, 30) und als solcher nicht verbalisiert. Aber Angst ist auch das, was nicht täuscht (101).[7] Deshalb ist der in einen Hirsch verwandelte Actaeon der Einzige, der noch weiß, wer er ist – im Gegensatz zu seinen Hunden und seinen Dienern. Indem Diana Actaeon Angst gegeben hat, hat sie sein Begehren bestraft.[8] Aber was genau war das Objekt seines Begehrens? Warum führen Lacan und auch Freud diesen Mythos überhaupt an? Eine mögliche Interpretation ist, dass gar nicht die Göttin in der Gestalt der schönen Jungfrau begehrt wurde, sondern die Wahrheit (lat. veritas), die sie verkörpert.[9] Lacan sagt: „Denn die Wahrheit erweist sich darin als vom Wesen her komplex, demütig in ihren Diensten und fremd der Realität, aufsässig gegen die Wahl des Geschlechts, verwandt mit dem Tod und, wenn man alles zusammennimmt, eher unmenschlich, Diana vielleicht…“ (513). Lacan setzt hier Diana mit der Wahrheit gleich. Und er folgt Freud, wenn er sagt „die Wahrheit [packt] im Munde Freuds besagtes Tier bei den Hörnern: ‚Ich bin also für Sie das Rätsel derjenigen, die sich, sobald sie erschienen ist, entzieht …“ (481).

Im letzten Teil dieses Textes von 1956, den Lacan „Die Ausbildung künftiger Analytiker“ nennt (512), zitiert er die bekannte Aussage Freuds, dass es sich bei Erziehen, Regieren und Psychoanalysieren um „unmögliche Unternehmungen“ handle bei denen das Subjekt solange verfehlt werde, wie es sich „in dem Spielraum, den Freud der Wahrheit vorbehält, aus dem Staub macht“ (513). Auf dem Weg der Wahrheit geht es also darum, sich nicht aus dem Staub zu machen. Aber dies bedeute im Umkehrschluss gerade nicht, dass man sich als Analytiker mit seinen Analysanden auf den staubigen Weg durch den Kamin begeben soll – in Anlehnung an die von „Anna O“ geprägte Metapher des chimney sweepings auf die Lacan am Ende der Sitzung vom 23. Januar 1963 in Seminar X anspielt.

Freud selbst, so Lacan, habe „das Ding“ (la Chose) fallenlassen, indem er wollte, dass Breuers Patientin diesem „alles sagt.“ Wenn es um die Wahrheit gehe, dann sage er sie zwar immer, so wird Lacan es einige Jahre später in Télevision (1974) formulieren, aber er sage sie nie ganz – denn dies sei unmöglich.[10]

In Seminar X verwendet Lacan verschiedene Jagdmetaphern: Netze, Schlingen, Knoten, Spuren und das Ausstreichen von Fährten. Doch auf dem Weg zur Wahrheit kann es keine Spuren geben, denen man folgen könnte: die Wahrheit ist das Einzige, was noch nicht geschrieben ist. Das Einzige, was stets noch erfunden werden muss. Dass, was in der Zukunft liegt – so formuliert es Jacques-Alain Miller in seiner hommage an Lacan vom Februar 2024.[11] Und deshalb beschäftigt sich Lacan so ausführlich mit der „unmöglichen Unternehmung,“ andere einem folgen zu lassen, um „die Stunde der Wahrheit zu finden“:

Treten Sie auf meinen Ruf hin in die Arena und heulen Sie mit meiner Stimme. Schon sind Sie, siehe da, verloren, ich widerspreche mir, ich fordere Sie heraus, ich stehle mich fort: Sie sagen, dass ich mich wehre (Lacan 2019a: 484).[12]

In einem Vortrag aus dem Jahr 1988 in den USA vor amerikanischen Psychoanalytikern bezeichnete Jacques-Alain Miller sich als underdog (Miller 1991: 84) und verwendet damit Lacans Hundemetapher. Miller war eingeladen, etwas von der Psychoanalyse zu erzählen, aber er wusste nicht recht was, denn zu groß schien ihm der Glaube seiner amerikanischen Zuhörer daran, bereits alles über die Psychoanalyse zu wissen. Wissen und Verstehen hilft auf dem Weg zur Wahrheit aber nicht: Die Natur der Wahrheit ist es, verschleiert zu sein und man kommt ihr nur näher, indem man den Schleier hebt, so Miller.[13]

Schluss

Es ist das Begehren, welches Actaeon in die Grotte und in sein Verderben führte. Da er keine Angst hatte, als er auf die Göttin traf, musste sie ihm von ihr erst gegeben werden. Bei uns Menschen steht die Angst jedoch bereits zwischen Begehren und Wahrheit. An diesem Ort verhindert sie, dass wir ungeschützt hinter den Vorhang blicken. Es macht nämlich einen Unterschied, ob der Akt des Vorhang-hebens allein vollzogen wird, wie bei Actaeon, der in Tizianos Gemälde in dem Moment eine Abwehrbewegung macht, in dem er wortwörtlich die nackte Wahrheit sieht, oder ob eine Annäherung an die Wahrheit im Rahmen einer ‚analytischen Aktion‘ (acte analytique) erfolgt. Das Begehren, die ganze Wahrheit erfahren zu wollen, ist dabei jedoch immer verfehlt.[14]

„Gerade durch dieses Unmögliche“, so Lacan in Télévision, „hängt die Wahrheit am Realen“ (Lacan 1974, 9). Die Angst, die sich zwischen das Begehren und die Wahrheit stellt, schützt uns also vor der ultimativen Konfrontation mit dem Realen. Wir verlieren durch sie zwar kurzzeitig unsere Sprache, aber immerhin nicht unsere menschliche Gestalt.

Diana und Actaeon. Tiziano Vecelli (Tizian) – 1556-1569 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Titian_-_Diana_and_Actaeon_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Literatur

Beyer, Judith. 2023. Perversion and the state. Lacan, de Sade, and why ‘120 Days of Sodom’ is now French national heritage. European Journal of Psychoanalysis 10 (1). https://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/articles/perversion-and-the-state-lacan-de-sade-and-why-120-days-of-sodom-is-now-french-national-heritage/#block-3

Freud, Sigmund. 1911. Varia. “Gross ist die Diana der Epheser” Zentralblatt für Psychoanalyse 2 (3): 158-159.

Harris, Oliver. 2017. Lacan’s return to antiquity. Between nature and the gods. London and New York: Routledge.

Katz, Maya Balakirsky. 2021. Great is the parable of Diana of the Ephesians! American Imago 78 (2): 389-418.

Klossowski, Pierre. 1980 (1956). Le bain de Diane. Paris. Gallimard.

Lacan, Jacques. 2010. Die Angst. Das Seminar, Buch X. 1962-1963. Übersetzt von Hans-Dieter Gondek. Wien und Berlin: Turia + Kant.

Lacan, Jacques. 2017 [1960/1961]. XXV. The relationship between anxiety and desire. In: Transference. The seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book VIII, übersetzt von Bruce Fink, 360-371.

Lacan, Jacques. 2019a [1955/1956]. Die Freud’sche Sache oder Sinn der Rückkehr zu Freud in der Psychoanalyse. In Jacques Lacan. Schriften I. Übersetzt von Hans-Dieter Gondek. Wien und Berlin: Turia + Kant, S. 472-513.

Lacan, Jacques. 2019b [1958-1959]. Desire and its interpretation. Seminar VI. Übersetzt von Bruce Fink. Medford, MA: Polity.

Lacan, Jacques. 2015 [1959]. Zum Gedenken an Ernest Jones. Über seine Theorien der Symbolik. In Jacques Lacan. Schriften II. Übersetzt von Hans-Dieter Gondek. Wien und Berlin: Turia + Kant, S. 205-238.

Lacan, Jacques. 1974. Télévision. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

Logan, Marie-Rose. 2002. Antique myth and modern mind. Jacques Lacan’s version of Actaeon and the fictions of surrealism. Journal of Modern Literature 25 (3/4): 90-100.

Malem, Sandrine. 2008. Un point de vue excentrique. Che vuoi ? 29 (1): 111-119.

Mathews, Peter. 2021. The symbolism of clothing. The naked truth about Jacques Lacan. CLC Web. Comparative Literature and Culture 23 (4): https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.3740

Miller, Jacques-Alain. 2009 [1980]. Another Lacan. Vortrag gehalten auf “Rencontre Internationale du Champ Freudien”, Caracas, Venezuela. Veröffentlicht in Symptom 10, übersetzt von Ralph Chipman.

Miller, Jacques-Alain. 1991. The analytic experience. Means, ends, and results. Vortrag gehalten 1988 in den USA. In Lacan and the subject of language, herausgegeben von Ellie Ragland. New York und London: Routledge, S. 83-99.

Miller, Jacques-Alain. 2016. La verité fait couple avec le sens. La Cause du Désir 92: 84-93.

Miller, Jacques-Alain. 2024. Lacan au présent. Théâtre de la Ville, Paris. 10. Februar https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hbDZO8kQ5GE&t=5318sOvid. Metamorphosen III. 155-252. Actaeon. Lateinisch-Deutsch. https://lateinon.de/uebersetzungen/ovid/metamorphosen-3/actaeon-2-155-191/ und https://lateinon.de/uebersetzungen/ovid/metamorphosen-3/actaeon-192-252/

[1] „‘Moi, la vérité, je parle‘ … C’est à ce titre que Lacan enseigne. Se faire comprendre, ce n’est pas enseigner, c’est l’inverse. On ne comprend que ce que l’on croit déjà savoir. Plus exactement, on ne comprend jamais qu’un sens dont on a déjà éprouvé la satisfaction. C’est dire qu’on ne comprend jamais que ses fantasmes. Et on n’est jamais enseigné sinon par ce que l’on ne comprend pas.” Wenn nicht anders angegeben, stammen alle Übersetzungen von mir.

[2] „La chose freudienne“ im Original oder „Die Freud’sche Sache oder Sinn der Rückkehr zu Freud in der Psychoanalyse“ (2019a [1956]) in der deutschen Übersetzung.

[3] In den früheren Seminaren V und VIII finden sich ebenfalls Diana-Referenzen.

[4] Lacan, Sem. X, S. 36: „Deshalb gibt es für mich nicht nur keinen Zugang zu meinem Begehren…“, siehe auch Lacan 2017: 361.

[5] In dieser Hinsicht ähnelt Lacans Botschaft der von Freud (1911), der selbst einen Diana-Text verfasste, welcher, so Katz (2021), bisher als eine unzureichende religionswissenschaftliche Abhandlung interpretiert wurde. Katz liest Freuds Text jedoch als eine versteckte Kritik an der damaligen Wiener Psychoanalyse.

[6] In der Sitzung vom 21. November 1962 unterscheidet Lacan „analytische Theorie“ von „analytischer Erfahrung“ und es ist die letztere, die er als die „Quelle“ (source) bezeichnet, zu der er seine Seminarzuhörer führen möchte.

[7] Der deutsche Kladdentext zu Sem X ist daher missverständlich. Er fasst den Inhalt des Buches wie folgt zusammen: „Es geht um die vielfältigen Erscheinungsformen der Angst in ihrem Täuschungs- und in ihrem Wahrheitscharakter.“ Nach Lacan hat die Angst keinen Täuschungscharakter – und ihr Bezug zur Wahrheit ist zentral, aber nicht als ein Aspekt der Angst, sondern vielmehr als das, was jenseits der Angst liegt.

[8] Siehe auch Lacan, Sem VIII: “In order that anxiety should be constituted, there has to be a relationship at the level of desire” (Lacan, 2017, 363; und: “… anxiety [angoisse], inasmuch as we consider it to be key to the determination of symptoms, arises only insofar as some activity that enters into the play of symptoms becomes eroticized – or, to put it better, is taken up in the mechanism of desire.” Lacan 2019b [1958-59], S. 12).

[9] Für andere Interpretationen siehe Klossowksi (1980 [1956]), Logan (2002) oder vergleichend Harris (2017).

[10] “Je dis toujours la vérité: pas toute, parce que toute la dire, on n’y arrive pas. La dire toute, c’est impossible, matériellement: les mots y manquent…“ (Lacan 1974, 9).

[11] “Non, tout n’est pas écrit. La vérité n’est pas déjà là, elle s’invente ; elle s’invente, elle est au futur…“ (Miller 2024).

[12] Ähnlich auch: „Was ist Lehren (enseigner), wenn es das, was es zu lehren gilt, nicht nur dem zu lehren gilt, der nicht weiß, sondern eben dem, der nicht wissen kann? Und man muss zugestehen, dass bis zu einem gewissen Punkt, geht man aus von dem, worum es sich handelt, wir hier alle im selben Boot sitzen (logés à la même enseigne)“ (Lacan, Sem X, 28).

[13] “… son statut natal est le voilage. La vérité comme telle est cachée et on n’y accède que par une levée du voile.” (Miller 2016, 87).

[14] Siehe auch Beyer 2023; Malem 2008; Mathews 2021.

Book Launch: Rethinking Community in Myanmar. 15th Int. Burma Studies Conference

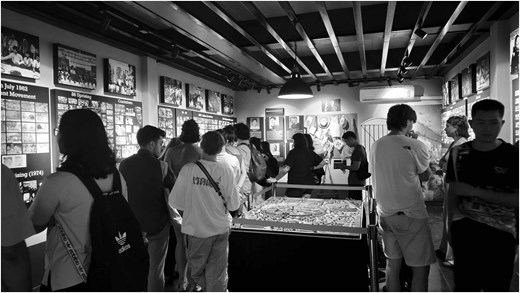

At the 15th International Burma Studies Conference, hosted at the University of Zurich, (9-11 June 2023), I launched my book Rethinking Community in Myanmar. Practices of We-Formation Among Muslims and Hindus in Urban Yangon.

Informal book launch in good company — while missing many from Myanmar

I wanted to celebrate the publication of my monograph: 10 years in the making if I count from the first days of fieldwork in 2012-2013. Good anthropological monographs take time and they are never the result of one indiviual only, even though writing can be a solitary process, particularly towards the end. I wanted to use the occasion of having over 200 Myanmar specialists gathering in one place, to say “Thank you” publicly to all the important people who could not be present in Zurich, but also to those who were able to share a glass of wine with me that day.

I set out by thanking my Muslim and Hindu interlocutors in Myanmar — there can neither be an anthropology nor an ethnography without the people ‘in’ (paraphrasing Tim Ingold). I owe them everything and I am glad that there will be an open access version of my book coming out towards the end of this year that will allow at least some of my interlocutors to download the book in Myanmar — I cannot bring it to them at the moment; not so much because it would be dangerous for me (it might be), but because I simply cannot take the risk of putting them into danger once I have left the country or their houses …

I then thanked my four research assistants — my KRA (Kachin Research Army) — and I explained to the audience of Burma/Myanmar experts that I profited enormously from them having conversations with my interlocutors about what it means to be a member of a minority in a majority Buddhist country. Listening in — as I am currently developing also in another context — is a methodologically fruitful approach to conduct fieldwork or carry out digital ethnography where fieldwork is not possible, because it decenters the anthropologist. What I am interested in mostly is “free-flowing talk” where my interlocutors do not try to guess what it is I want from them (in terms of what they might be expected to tell me), but where I can simply follow them having conversations with one another. Since all of my research assistants were Christian Kachin women, it was not religion they shared with my interlocutors (who were Muslims and Hindus), but the experience of being ‘slotted in’ as members of ‘communities’.

I also thanked my colleagues in Myanmar who had been professors of Anthropology at the University of Yangon prior to the attempted military coup in February 2021. Thanks to them, my PhD students received research visa, thanks to them, I had the opportunity of teaching and learning from young anthropology students, and thanks to them I learned a lot about the history of the discipline in Myanmar and about the history of the University of Yangon. I truly hope that one day they will be able to return to their professional jobs — which they cherished a lot, and to their students whom they loved.

None of these people could be with my family, my PhD students, and the other Myanmar scholars that day.

Thanking those who were there

I was happy to be surrounded by many friends, who had helped in different ways to bring this book to fruition: many of my colleagues had read draft chapters, some had written reviews or are going to write them. Alicia Turner gave some introductory words — she knows the book very well as she has written the most constructive and helpful review that made the final product so much better!

The managing editor of NIAS Press, Gerald Jackson, had come from Copenhagen to Zurich with his research assistant Julia Heinle and with a lot of amazing books on Southeast Asia and on Myanmar in tow. He took my book project on board and steered it smoothly through the production process in not even two years from the submission date!

My PhD students who are working on Myanmar, were all present, too. We discussed my material just as much as we discussed theirs. They all completed long-term ethnographic fieldwork in or on Myanmar and I can’t wait to see their own books!

And — last but not least — my family — who accompanied me from 2012 onwards and carried out their own research projects in Yangon: on the politics of cultural heritage in one case and on what it means to go to a local school in Chinatown in Yangon in the other case.

Thank you to everyone who was there that evening — be it in spirit or in the flesh — I am very grateful for the support I have received in the last decade. I hope the book will be useful to many.

We-formation. Reflections on methodology, the military coup attempt and how to engage with Myanmar today. Lecture in Paris, 16 May 2023

In this invited lecture, I will discuss my concept of “we-formation” in regard to three different topics: First, as anthropological theory and methodology; Second, as a way to make sense of the resistance against the attempted military coup and third in regard to the possibility of a public anthropology of cooperation in these trying times.

First, I will explore the concept in regard to its theoretical and methodological innovativeness, taking an example from my Yangon ethnography as illustration. We-formation, I argue in my book Rethinking community in Myanmar. Practices of we-formation among Muslims and Hindus in urban Yangon, “springs from an individual’s pre-reflexive self-consciousness whereby the self is not (yet) taken as an intentional object” (8). The concept encompasses individual and intersubjective routines that can easily be overlooked” (20), as welll as more spectacular forms of intercorporeal co-existence and tacit cooperation.

By focusing on individuals and their bodily practices and experiences, as well as on discourses that do not explicitly invoke community but still centre around a we, we-formation sensitizes us to how a sense of we can emerge (Beyer 2023: 20).

Second, I will put my theoretical and methodological analysis of we-formation to work and offer an interpretation of why exactly the attempted military coup of 1 February 2021 is likely to fail (given that the so-called ‘international community’ does not continue making the situation worse). In the conclusion of my book I argue that the “generals’ illegal power grab has not only ended two decades of quasi-democratic rule, it has also united the population in novel ways. As an unintended consequence, it has opened up possibilities of we-formation and enabled new debates about the meaning of community beyond ethno-religious identity” (250).

Third, I will discuss how (not) to cooperate with Myanmar today. Focusing on what is already happening within the country and amongst Burmese activists in exile, but also what researchers of Myanmar from the Global North can do within their own countries of origin to make sure the resistance does not lose momentum. In this third aspect, I take we-formation out of its intercorporeal and pre-reflexive context in which I came to develop the concept during my fieldwork in Yangon and employ it to stress a type of informed anthropological action that, however, does not rely on having a common enemy or on gathering in a new form of ‘community’ that has become reflexive of itself. Rather, it aims at encouraging everyone to think of one’s own indidivual strengths, capabilities and possibilities and put them to work to support those fighting for a free Myanmar.

You can purchase my book on the publisher’s website: NIAS Press.

Here’s the full programme of the Groupe Recherche Birmanie for the spring term 2023:

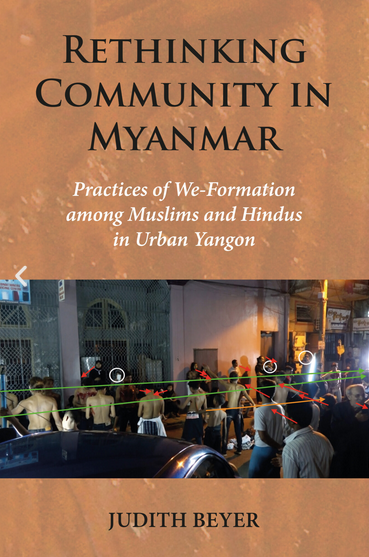

“Rethinking community in Myanmar. Practices of We-Formation among Muslims and Hindus in Urban Yangon” (NIAS Press 2023) has arrived!

‘Community’, I argue in my new anthropological monograph, was actively turned into a category for administrative purposes during the time of British imperial rule. It has been put to work to divide people into ethno-religious selves and others ever since.

Rather than bestowing on community some sort of positivist reality or deconstructing the category until nothing is left, my aim in this book is to shift the angle of approach: I acknowledge that community (for reasons that can usually be traced historically) feels real to and is meaningful for individuals. Their experiences and their struggles to engage with community are no less real. Through their own classificatory practices, my interlocutors — Muslims and Hindus in urban Yangon — demonstrate that they reason and reflect on symbols and meanings in their own culture as much as anthropologists do. But my approach goes beyond a social constructivist concern over how terms such as community are used, and also beyond a representational approach in which actors are subjected to culture as a system of meaning.

When I talk about the work of community (drawing on Nancy 2015), I reflect on the ways in which individuals accommodate ‘community’ in their acts of reasoning, meaning-making and symbolization. The way my interlocutors in Yangon see and talk about themselves has a historical context that begins in nineteenth-century England, encompasses British colonial India and later Burma itself, and extends into presentday

Myanmar. I then widen the emic perspective of my interlocutors and offer a novel way of describing how a we that does not neatly map onto or overlap with a homogeneous social group is generated in various situations.

What I call we-formation encompasses individual and intersubjective routines that can easily be overlooked, as well as more spectacular forms such as the intercorporeal aspects of the ritual march I described earlier. Attending to such sometimes minute moments of co-existence or tacit cooperation is difficult, but doing so can help us understand how community continues to have such an impact on the everyday lives of our interlocutors, not to mention on our own analytical ways of thinking about sociality.

By focusing on individuals and their bodily practices and experiences, as well as on discourses that do not explicitly invoke community but still centre around a we, we-formation sensitizes us to how a sense of we can emerge .

You can purchase the book on the publisher’s website: NIAS Press.

Rethinking Community in Myanmar. New Book out soon!

Announced for November 2022 with NIAS Press:

Rethinking Community in Myanmar. Practices of We-Formation among Muslims and Hindus in Urban Yangon.

This is the first anthropological monograph of Muslim and Hindu lives in contemporary Myanmar. In it, I introduce the concept of “we-formation” as a fundamental yet underexplored capacity of humans to relate to one another outside of and apart from demarcated ethno-religious lines and corporate groups. We-formation complements the established sociological concept of community, which suggests shared origins, beliefs, values, and belonging. Community is not only a key term in academic debates; it is also a hot topic among my interlocutors in urban Yangon, who draw on it to make claims about themselves and others.

Invoking “community” is a conscious and strategic act, even as it asserts and reinforces stereotypes of Hindus and Muslims as minorities. In Myanmar, this understanding of community keeps self-identified members of these groups in a subaltern position vis-à-vis the Buddhist majority population. I demonstrate the concept’s enduring political and legal role since being imposed on “Burmese Indians” under colonial British rule. But individuals are always more than members of groups. I draw on ethnomethodology and existential anthropology to reveal how people’s bodily movements, verbal articulations, and non-verbal expressions in communal spaces are crucial elements in practices of we-formation. Through participant observation in mosques and temples, during rituals and processions, and in private homes I reveal a sensitivity to tacit and intercorporeal phenomena that is still rare in anthropological analysis.

Rethinking Community in Myanmar develops a theoretical and methodological approach that reconciles individuality and intersubjectivity and that is applicable far beyond the Southeast Asian context. Its focus on we-formation also offers insights into the dynamics of resistance to the attempted military coup of 2021. The newly formed civil disobedience movement derives its power not only from having a common enemy, but also from each individual’s determination to live freely in a more just society.

Teaching Hannah Arendt in 2021

Hannah Arendt is one of the best-known political theorists of the 20th century. Her books and her theoretical arguments emerged in dialogue with ancient philosophers (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle) and modern German thinkers (Kant, Hegel), as well as with her own university teachers (Heidegger, Husserl, Jaspers). Arendt never saw herself as a philosopher, but as a theoretician of the political. The topics she dealt with are today more topical than ever before and her books are being read across disciplines.

Hannah Arendt wrote on totalitarianism, statelessness, human community, and freedom and responsibility. In her work she processed her own experience as a Jew in Germany, as a stateless person in World War II, as a migrant in the USA, as a woman in male-dominated academia and as an attentive observer of an increasingly globalized post-war world.

This semester I am teaching some of her main theoretical themes to a group of BA students at the University of Kontsanz. We will not only embed Arendt’s texts in their historical context, but also to think through and with her arguments using current examples — ranging from the covid pandemic to state terror in Myanmar. Hannah Arendt was interested in the basic conditions of human existence: whenever these are questioned or radically transformed, her work offers a fruitful starting point.

“Why read Hannah Arendt now?” (2018) asks the author Richard Bernstein in his recent book. Answer: because she is “the thinker of the hour” (according to the German translation of the book).

Here is the Syllabus to my course (in German).