1. The force of custom. Law and the ordering of everyday life in Kyrgyzstan

In this talk, I offer a unique critique of the concept of ‘postsocialism’, a new take on the concept of legal pluralism, and a plea to bring ethnomethodological approaches into correspondence with ethnographic data. Drawing on a decade of anthropological fieldwork and engagement with Central Asia, I will focus on describing how my informants in rural Kyrgyzstan order their everyday lives and rationalize their recent history by invoking the force of custom (Kyrgyz: ‘salt’).

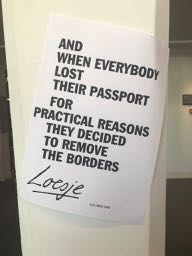

Although ‘salt’ is often blamed for bringing about more disorder and hardship than order and harmony, as I will exemplify with the example of mortuary rituals, it allows my informants to disavow responsibility for their actions by pushing a model of ‘how things get done here’ to the front. Invoking ‘salt’ enables actors even as they claim to be constrained by it, it opens up possibilities to conceptualize, classify, and contextualize large- and mid-scale developments in an intimate idiom. It also is a way to communicate to others that one is an expert in and of one’s own culture. An ethnomethodological perspective, as I pursue it, challenges a conception of social order as hidden within the visible actions and behaviours of members of society. Rather, it examines how members produce and sustain the observable orderliness of their own actions.

- Le 12 mars 2019 de 16h à 18h – Université Paris-Nanterre, Département d’anthropologie, salle E105, 200, avenue de la République, 92001 Nanterre

2. The arrival of the Indian Other. On classifying minorities in Burma

Migrants from India have arrived in Burma from pre-colonial times onwards up until the Second World War. They crossed the Bay of Bengal out of personal economic endeavours, but having been categorized collectively by the British colonial state already before they embarked on the steamships to Rangoon, their collective identities travelled with them. Next to looking for work, other migrants relocated there to make use of parcels of land that were given to them as a reward for their services in the colonial apparatus or in the Indian army; yet others took up positions in the higher echelons of the administration in Burma. These people entered a Buddhist polity that had been shaped by centuries of hierarchical modes of royal governance – one which included Muslims and other ethno-religious minorities. This talk traces the different types of classifications and reclassifications that were projected onto and subsequently appropriated by ‘Indian migrants’ in order to shed light on the current situation of ethno-religious minorities in contemporary Myanmar, particularly in the city of Yangon.

Dans le cadre du Séminaire “Dialogues entre recherches classiques et actuelles sur l’Asie du Sud-Est“

- Le 14 mars 2019 de 10h à 12h – EHESS, SR 737, 54, boulevard Raspail, 75006 Paris

3. Accountability and justice in asylum claims. Debating the issue of Rohingya statelessness in British courts.

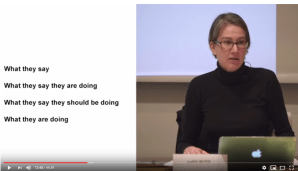

Accountability is a reflexive technique by means of which actors realize and lay claim to their actions. In order to be recognizable, accountability “depends on the mastery of ethno-methods” (Giddens 1979: 57; 83). If, as Garfinkel put it, “[a]ny setting organizes its activities to make its properties as an organized environment of practical activities detectable, countable, recordable, repeatable, tell-a-story-aboutable, analysable – in short, accountable” (1967, 33; italics in original), then so-called ‘screening interviews’ in asylum cases of stateless Rohingya are a challenge to this principle as they are defined by non-knowledge about the other. When UK border agents and Rohingya meet, their ‘membership’, which forms the basis of all co-production of action (and knowledge) in ethnomethodology, needs to be established ad hoc in the interview situation. What we can learn from those ‘first contact’ encounters and the subsequent travelling of a Rohingya asylum seeker’s file through the court system, is, I argue, how accountability is constantly being produced through interaction and how, as an important by-product of this production process, not only a ‘case’ is decided, but also the validity of the state’s own account is rendered plausible.

Dans le cadre de la conférence co-organisée par Yazid Ben Hounet et Judith Beyer “Claiming Justice after Conflict: The Stateless, the Displaced and the Disappeared at the Margins of the State”

- Le 15 mars 2019 de 10h15 à 11h15 – FMSH, Salle A3-50, 54 Bd Raspail 75006 Paris

4. On little and grand narratives in Central Asia

In this keynote speech, I engage with the conference topic of “challenging” and even “disturbing” “Grand Narratives” through an investigation of the tradition of orality and the usage of oral history in Central Asia. These are two interlinked endeavours, as oral tradition has been investigated “as history” (Vansina) and oral history understood as “the voice from the past” (Thompson). Anthropologists (of Central Asia) investigate tradition as “a site of necessary engagement that aggregates people, … informs policy, public debates, law, and representation, and is – despite its often enough strategic inception – affectively powerful” (Beyer and Finke forth. in Central Asian Survey). Examples from Central Asia show how “oral tradition”, especially when mediated by state and media apparatus, can take on “grand narrative” qualities. Moreover, in contrast to how oral history has been treated in the past, namely as history “from below”, of “the everyday” and by “the little guys” (Graeber), thus as “little narrative”, as I will call it, it is worth exploring in what ways this method of ethnographic and historical inquiry has the capacity to yield “grand” results.

Dans le cadre de la Conférence “CASIO 2.0 : Disturbing Grand Narratives” organisée par l’EHESS et ZMO (Berlin).

- Le 28 mars 2019 de 10h à 12h – PSL, Salle du Conseil, 60, Rue Mazarine, 75006 Paris.