Wer sind die Menschen, die zur Zeit in Myanmar auf die Straße gehen, um gegen den Militärputsch vom 01. Februar 2021 zu protestieren? In einem Radiointerview mit Radio Eins rbb in deren Reihe “Die Profis” (“Die Sendung mit der Maus für Erwachsene”), bei der es vor allem um Stimmen aus der Wissenschaft geht, erkläre ich “Wer in Myanmar protestiert“, sowie weitere Hintergründe der aktuellen Situation in Myanmar und was die “internationale Gemeinschaft” tun kann, um die Menschen zu unterstützen.

Category Archives: activism

Article for OpenDemocracy: On intergenerational solidarity and intergenerational trauma in Myanmar

In this post I highlight a special dynamic linking the different generations within the ongoing protest movement in Myanmar: The current protests combine the experiences the older generation has had under decades of military rule with the digital know-how of the younger generation that grew up during a decade of partial democratic freedom.

For many years, resistance to the military regime centred around the iconic figure of General Aung San and his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, who is currently under arrest. This is now changing. The form of resistance is no longer just a “family affair”, I argue. The organization of protests is decentralized, without clear leaders. It involves all generations and brings together very different groups. The rallying cry now resounding on Myanmar’s streets is ‘You messed with the wrong generation.’

Interview with Al Jazeera on statelessness, human rights, Myanmar, Kyrgyzstan

”Why are human rights defenders being targeted?” asked Al Jazeera Rajat Khosala from Amnesty International, a specialist for advocacy and policy, Tobi Cadman an International Human Rights Lawyer and myself. Al Jazeera’s “Inside Story” draws a bleak picture of the human rights situation worldwide with repression in authoritarian states increasing. Human rights defenders are particularly being targeted. I reported about the current situation of human rights activism in Kyrgyzstan and Myanmar where we have just witnessed a military coup. I also spoke about the situation of the 10-15 million de-facto stateless people worldwide who cannot even claim human rights as they lack a nationality.

I explained the difference between de jure and de facto statelessness and emphasized that the roles of the state system and that of the United Nations need to be rethought when it comes to statelessness in particular and how we can all ensure the adherence to human rights in general. We also touched upon the importance of staying connected digitally as activism is increasingly being carried out online.

In the name of stability. On the coup in Myanmar

Myanmar’s immediate neighbours have reacted very reluctantly in regard to the military coup that began on February 1 2021. Whereas ASEAN member-states have largely declared the coup an “internal affair” into which they would rather not get involved, China said it had “noted” the events and urged the country to uphold “stability”.

Stability, however, is not a neutral or entirely positive concept I argue in this German-language article for the daily newspaper TAZ: it is possible to justify not only repression and coups in Myanmar with it, but even the recent genocide of the ethnic Rohingya.

Stability has been a key metaphor during previous military dictatorships as well: Until 2010, for example, the second out of four so-called “national causes” that the military government under General Than Swe promoted under the title “The People’s Desires” read “Oppose those trying to jeopardize the stability of the state and the progress of the nation.”

It had also been Aung San Suu Kyi herself who, in December 2019 in her role as a member of her country’s delegation at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) left the more legalistic arguments to the specialists for international law, and challenged the legitimacy of the case on the basis of harmony ideology.

In the name of stability,she argued that the principal judicial organ of the United Nations should refrain from interfering in Myanmar’s domestic affairs.

In my recent article, I thus hold that invoking ‘stability’ is more in line with what the military government is advocating than it it is supportive of the civil resistance that is currently beginning to form.

Read the full post in TAZ.

Towards an anthropology of statelessness

As part of my tenure-track evaluation I held a public lecture at the end of April 2020 at the University of Konstanz on the topic of statelessness. I am currently in the process of drafting a funding application that would enable me to work towards developing how an anthropology of statelessness could look like.

I’d like to mention a couple of thoughts here to help me think through this potential new subdiscipline and to raise awareness of what I think is a structural lack at two different levels:

1) within the very concept of the nation-state and

2) within the anthropology of the state.

While the first concerns the prime object of analysis of the anthropology of the state, the second concerns a structural lack within how we have up to date researched that prime object.

I argue that statelessness has so far been approached as something ‘lacking’ in the constitution of those who do not have a nationality — for whatever reason (and there are many). Thus, activists, practitioners, (I)NGOs and other global actors have focussed their attention on ‘fixing’ the lack of the stateless by trying to make sure they, too, receive nationality (or citizenship; I won’t go into details here as to where these concepts overlap and where they don’t). In doing so, statelessness has remained an ‘anomaly’ — something that needs ‘fixing’. But we have neglected (almost entirely) in our scholarly analyses (these are mostly legal, political and almost none anthropological up to date) that it might not be the stateless who need ‘fixing’, but the nation-state itself. This argument has been made by the political theorist Phil Cole (2017), for example, but needs to be taken seriously and thought through in legal and political anthropology as well for it might provide novel insights into the anthropology of the state.

Understanding statelessness as a structural lack of nation-states

In my tenure lecture, I have argued that statelessness cannot be researched at the ‘heart of the state’ (Fassin) or at its ‘margins’ (Das and Poole) where anthropology has so far located its objects of inquiry when studying the state in a transversal or tangential (Harvey) manner. It rather points to what I – with Lacan – would define as a structural lack in how nation-states are set up and operate. As such, this type of lack is not meant to be ‘filled’. As much as statelessness is not a mode of being that could be ‘fixed’, the structural lack that statelessness opens up  within the concept of the nation-state is not meant to be ‘filled’. It is there on purpose, I argue. Treating statelessness not as anomaly, but as an intentional product in the way the state operates allows for new insights into the state as much as it will move our engagement with the phenomenon of statelessness beyond appeals of ‘fixing’.

within the concept of the nation-state is not meant to be ‘filled’. It is there on purpose, I argue. Treating statelessness not as anomaly, but as an intentional product in the way the state operates allows for new insights into the state as much as it will move our engagement with the phenomenon of statelessness beyond appeals of ‘fixing’.

As much as statelessness is not a mode of being that could be ‘fixed’, the structural lack that statelessness opens up within the concept of the nation-state is not meant to be ‘filled’.

Despite the fact that we have international conventions in place since the mid 1950s, and despite the fact that more and more states have ratified these conventions and are closing legal loopholes: statelessness continues to exist and in many parts of the world, including Europe, its numbers are increasing. It remains one of the most overlooked human rights violations and it won’t go away, no matter how much the UN wants it to. The project I am currently drafting would bring legal scholars, anthropologists and practitioners together and study the structural lack of statelessness as an intrinsic component of the nation-state.

From stateless societies to stateless individuals

Anthropologists have historically dealt with stateless societies as part of Europe’s (and America’s) colonial politics of expansion and exploitation. Most ethnographic monographs centred on ‘acephalous’ ethnic groups or tried to grapple with understanding how groups organized and interacted with one another without a clear leadership or someone ‘in power’. After the demise of colonialism, such work has almost completely come to a halt; the state has come to tighten its grip on ethnic groups to such an extent that there is, by now, no place on earth that would not feel its eery presence. This includes hunter-gatherer societies (Sapignoli 2018) and sedentary tribes (Girke 2018) in rural Africa as much as agrarian groups in Southeast Asia (Scott 2010). However, statelessness has remained an immanent phenomenon worth anthropological attention. My argument is, however, that nowadays we need to focus on stateless individuals (in the sense of an anthropo-logy) more than on stateless societies (in the sense of an ethno-logy). While many groups are de facto stateless (e.g. Rohingya), the de jure status of statelessness is granted to individuals only. In line with an existential anthropology (Jackson and Piette 2015), my aim is to research statelessness not as a historical leftover of group encounters with the (colonial) state, but as an existential human condition that allows us to understands a structural lack of the contemporary nation-state.

Stay tuned …

On the politics of ‘standing-by’. Post for Public Anthropologist

In the arena of national politics, there is a widespread moral expectation that citizens should be informed about politics and exert agency to “take part” rather than merely “standing by” apathetically. Especially in light of the recent (ethno-)nationalist shifts towards the right in Europe, there has been an increasing demand on people to not close their eyes to the right’s attempts to claim the streets … In ethnomethodological studies, the acquisition of “membership knowledge” is regarded as a prerequisite for being able to analyze the practices of the actors the researcher intends to study. But what kind of knowledge is there to be acquired if a crowd consists mostly of by-standers?

In this  recent post for the new blog of Public Anthropologist, a journal devoted to providing a space “beyond the purely academic realm towards wider publics and counterpublics”, I reflect on having spent a Saturday in March 2019 in Paris, encountering three different types of manifestations in which I became involved as a by-stander. I argue that while the investigation of movements, resistance and direct action remains essential, we should not forget to “assume the perspectives of those on the side-lines. Because it is there that the majority of us become part of public politics.”

recent post for the new blog of Public Anthropologist, a journal devoted to providing a space “beyond the purely academic realm towards wider publics and counterpublics”, I reflect on having spent a Saturday in March 2019 in Paris, encountering three different types of manifestations in which I became involved as a by-stander. I argue that while the investigation of movements, resistance and direct action remains essential, we should not forget to “assume the perspectives of those on the side-lines. Because it is there that the majority of us become part of public politics.”

You can read the full blog post here.

Teaching on Statelessness

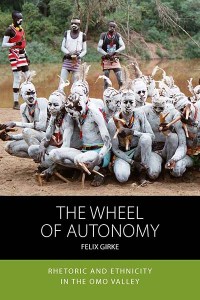

This summer term, I will be back at my University, teaching one course on “Statelessness” at the BA-level for our anthropology and sociology students. I am particularly looking forward to the two guest lectures: One by Felix Girke (University of Konstanz) who will be exploring how anthropology has traditionally worked with “stateless” people during colonial times and what has happened in areas and to people in South Omo in Southern Ethiopia where the modern state had been absent for a long time, but has now become a cruel force.

The second guest lecture will be given by Kerem  Schamberger from the University of Munich and a political activist, who will present his new book “Die Kurden. Ein Volk zwischen Unterdrückung und Rebellion” (together with Michael Meyen) during the seminar.

Schamberger from the University of Munich and a political activist, who will present his new book “Die Kurden. Ein Volk zwischen Unterdrückung und Rebellion” (together with Michael Meyen) during the seminar.

Here is the course syllabus (in English, the seminar will be held in German)

Research Granted: How to become an activist in Myanmar and South Africa

The German Research Foundation (DFG) has granted 4 PhD positions at the University of Konstanz for a joint comparative research project on “Activist becomings in South Africa and Myanmar.“ I will supervise 2 PhD projects on Myanmar while my colleague, Thomas Kirsch, will supervise two projects on South Africa. We hope that the outcomes will provide new knowledge concerning practices of democratic participation in the midst of urban and postcolonial crisis.

The project is definitely a precious contribute to the infrastructural turn and could serve as a model of research in very different parts of the world and in different social and political circumstances (anonymous reviewer)

With a focus on material and non-material infrastructure, our project seeks to provide new theoretical and methodological tools to study political formations, thereby contributing to an anthropology of activism, infrastructural studies, political anthropology, anthropology of democracy and African and Asian studies. The research project explicitly seeks to disseminate knowledge and build bridges between scholarly research and activism – something I am really excited about!