Our collaborative article “Exiled Activists from Myanmar: Predicaments and Possibilities of Human Rights Activism from Abroad“, published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice (Oxford University Press), is finally out! 🎉

I am very proud of the work that my colleague Samia Akhter-Khan, my two Ph.D. students Sarah Riebel and Nickey Diamond, another author from Myanmar (who has to use a pseudonym for reasons of safety), as well as myself have managed to achieve under very difficult circumstances.

This article was born out of necessity to engage with the topic of exile. None of us had ever wanted to study yet alone experience this existential state of being. The empirical material we draw on in this article stems from autoethnographic accounts (Nickey Diamond and Demo Lulin), semi-structured interviews and conversations with around forty exiled activists currently residing in Thailand, the US, the UK, Austria, and Switzerland (Samia Akhter-Khan and myself) as well as extensive ethnographic work with exiled activists in Thailand (Sarah Riebel).

In this article, we put forward the concept of the ‘exiled activist’ to highlight the predicaments and the possibilities that practicing human rights activism from abroad bring with it. From our analysis, we have developed three so-called ‘practitioner points’ that might guide INGOs, NGOs, states and other bodies to properly relate to exiled activists from Myanmar. These are:

1. Develop trauma-informed support systems for exiled activists by integrating psychosocial care and peer-based mental health resources into human rights programming and diaspora organizing.

2. Adapt partnership models to accommodate the shifting positionality of exiled activists, recognizing their need for secure digital platforms, flexible funding, and shared decision-making across borders.

3. Acknowledge and navigate political divisions within diverse groups of exiled activists – such as differing views on the National League for Democracy, the military, or the Rohingya – by avoiding assumptions of unity and instead fostering inclusive collaboration that respects diverse activist trajectories and lived experiences.

We have made our article openaccess so that everyone is able to download it. Currently, we are working on a shorter version in Burmese/Myanma, to also allow those who do not speak English to read about this important topic.

Thank you to all exiled activists who have participated in this study, trusted us and shared their stories – and to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the support of scholars at risk over the last years!

Author Archives: Judith Beyer

Intro to Anthro for Myanmar Students (and others)

On the occasion of what would have been Aung San’s 111th birthday, I release a video lecture which I have given in late 2021 to anthropology students from Myanmar after the Myanmar military attempted a coup on 1 February 2021.

Some of my own students and tens of thousands more had to go into hiding once the military began occupying their universities and took over their cities. With their professors resigning from their positions out of protest, their education came to a sudden, abrupt halt. Having to leave their dormitories and sitting in their parents’ homes again, or having to flee Yangon, Mandalay and other bigger cities in which they had until then studied, they still longed to continue their studies.

This lecture was an effort to support them in this endeavour, albeit without being able to substitute for what they had lost. Moreover, it became evident over the course of the online sessions, that many could not concentrate due to the ongoing violence and the many new tasks they had to adhere to in order to secure their own living or contribute to the livelihood of their families. It is hard to study while having to cope with trauma.

In the lecture, I discuss the concept of ‘guerilla anthropology’ as a way to educate each other while in hiding or from abroad; education as a subversive act of resistance and as refusal to give in. In the main part of the lecture, I cover both the history of anthropology and the role of history in anthropology.

By 2026, several so-called “virtual universities” have taken over from what had been a first effort of mine and fellow anthropologists back then. They have now build a systematic online education path for thousands of Myanmar students. Moreover, some of my own former students from the Unviersity of Yangon have become educators themselves and now teach schoolchildren in the Myanmar-Thai border region. Others have left the country to pursue their own education – all hope to be able to return to Myanmar one day…

May their dream come true!

#Contra AI 🤖 – Arguments against AI

Since I am human, I have an intrinsic motivation to understand. Since I am an anthropologist, I have an intrinsic motivation to understand other humans. Since many humans seem more and more motivated to hand their intrinsic motivation to a machine, I am now intrinsically motivated to not only understand how AI operates and what its effects are, but who the humans behind the technology are and to what they might put AI to use.

Since I am also a university professor, I am faced with the topic of AI almost every day. I have noted three common ways of how academia relates to the issue so far:

a) AI is the future and everything will be great

b) we are doomed and we can’t win against AI

c) who cares about AI ?

So I have started to gather texts on AI, particularly those written by scholars or by journalists engaging with academic literature. The result (so far): AI is stupid and as such maybe not so different from humans after all. But: it feeds off our knowledge and it learns from our mistakes. It also gets better in duping us, luring us in and making us believe that there is indeed ‘someone’ on the other side. There is not.

Here is my list of collected texts (tbc.) which I enjoyed reading and which I recommend to everyone, whether you are a) b) or c).

Order on fair use

Shutdown resistance in reasoning models

Expressing stigma and inappropriate responses prevents LLMs from safely replacing mental health providers.

What Happens After A.I. Destroys College Writing?

Why we fear AI: On the Interpretation of Nightmares

Surface Fairness, Deep Bias: A Comparative Study of Bias in Language Models

Geoffrey Hinton’s speech at the Nobel Prize banquet, 10 December 2024

Echte Emotionen. Generative KI und rechte Weltbilder

Assuring an accurate research record

Lawyer caught using AI-generated false citations in court case penalised in Australian first

Why Even Try if You Have A.I.?

Help Sheet: Resisting AI Mania in Schools

Against the Uncritical Adoption of ‘AI’ Technologies in Academia

When Knowledge Is Free, What Are Professors For?

Kritik der Digitalisierung. Technik, Rationalität und Kunst

Nature: Major AI conference flooded with peer reviews written fully by AI

I’m Kenyan. I Don’t Write Like Chat GBT. Chat GBT Writes Like Me

A New Direction for Students in an AI World (200-page report)

Measuring the Impact of Early-2025 AI On Experienced Open-Source Developer Productivity

A.I. Companies are Eating Higher Education

to be continued …

Open Acess: “Asylum Interviews in the UK”. Published in Social Anthropology

My new article “Asylum Interviews in the UK. The problem of evidence and the possibility of applied anthropology” has just been published with Social Anthropology / Anthropologie Sociale (33/3: 51-65).

In this article, I interrogate the process how evidence is established in asylum procedure by engaging with anthropological and socio-legal literature on evidence and credibility assessments. Drawing on ethnomethodology, I analyse asylum interviews and show in what ways evidence can be understood as the result of an asymmetrical co-construction. As a result of this procedure, the individual applicant disappears and a ‘case’ is established.

Anthropologists who write country of origin reports based on such ‘case material’ for tribunals and courts can highlight the asymmetries in evidence-making and question the very categorisations through which the state operates. The article contributes to ongoing debates on the role of anthropologists and their knowledge as experts in court.

It is open access and can be downloaded here.

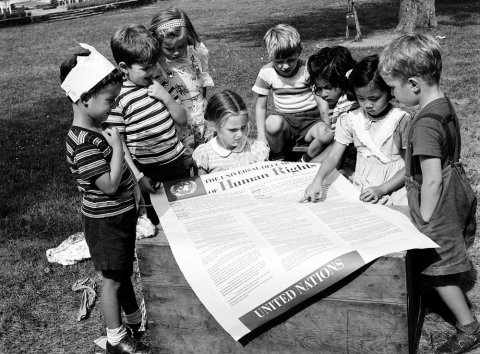

Crimes against commonality

Before all other forms of membership, we are “all members of the human family”, as the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has specified. Thus, the international legal concept of crimes against humanity is crucial because all war crimes are predicated on the fact that those committing these atrocities are enabled once they succeed in establishing difference that makes us forget our human commonality.

We cannot but make do with what the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has called the imaginary order – the way in which we try to relate to others by looking for similarities and differences, mainly in order to acknowledge ourselves. We need the ‘other‘ to sustain ourselves as the I(ndividual) we imagine ourselves to be.

The imaginary order is the order of world-making in the sense of Hannah Arendt (1959) for whom the world is not ‘out there‘, but rather that which arises between people in discourse, as I will develop in an upcoming presentation. We have to keep engaging with others, irrespective of the fact that we will never really understand each other entirely. But we are obliged to keep trying. There is no other way.

“For the world is not humane just because it is made by human beings, and it does not become humane just because the human voice sounds in it, but only when it has become the object of discourse … We humanize what is going on in the world and in ourselves only by speaking of it, and in the course of speaking of it, we learn to be human” (Hannah Arendt, 1959, 24-25)

Human commonality is already there from the beginning, transcending all dichotomies, whereas difference is something we can only ever bring about consciously. What we have in common and what makes us human is that we are split by language, as Lacan argued. If we acknowledge this, we might be able to include the other not as an opposite ‘they’ but as part of our own unconscious: we are always other to ourselves first.

Boat is a man

2024 has been the deadliest year for migrants trying to cross the Channel in small boats to reach the UK, with 69 deaths reported (Refugee Council 2025). British politicians have been referring to the circumstances under which people migrate to the UK as “the small boat crisis“ and subsequently made a “small boat deal“ with countries such as Ruanda, to which they wanted to ship people to.

Before the Labour party came to power, they accused the Tories of “having lost control of small boat migration“. Now, that they are in power, they claim that there is “no nice or easy way of doing it“. Getting rid of people who came by boat…

But what if boat were a man?

I recently bought a small booklet filled with Walter Benjamin’s short stories. Tales out of loneliness is its subtitle. In it, there is a 1-page story entitled How the Boat was Invented and Why It Is Called ‘Boat‘. It follows a similar pattern as Benjamin’s short story on Why the elephant is called ‘elephant‘ that immediately precedes the story about the boat.

Here’s how Boat’s story goes:

Before all the other people, there lived one person and he was called Boat. He was the first person, as before him there was only an angel who transformed himself into a person, but that is another story.

So the man called Boat wanted to go on the water — you should know that back then there was a lot more water than today. He tied himself to some planks with ropes, a long plank along the belly, that was the keel. And he took a pointed cap of planks, which was, when he lay in the water, at the front — that was the prow. And he stretched out a leg behind him and navigated with it.

In this manner he lay on the water and navigated and rowed with his arms and moved very easily through the water with his plank cap, because it was pointed. Yes, that is how it was: the man Boat, the first man, made himself into a boat, with which one could travel on water.

And therefore — of course that is quite obvious — because he himself was called Boat, he named what he had made ‘boat‘. And that is why the boat is called ‘boat‘.

(Walter Benjamin, 26 September 1933; published posthumously)

The “small boats crisis” is Boat’s crisis, the crisis of man. This is the elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about. Because they do not know why the elephant is called ‘elephant‘ either.

Philosophy saves lives.

Eid Mubarak … in Myanmar

Eid Mubarak, Айт маарек болсун, Ramadan kareem, Ein gesegnetes Ramadanfest … to all my friends, colleagues, interlocutors across the world who are celebrating today!

This year, my thoughts are with all Muslims in Myanmar, particularly those most heavily affected by the earthquake. After a month of fasting, which is physically and psychologically challenging, instead of celebrating with their family and friends, they are searching for or burying their loved ones. For many children there might be no new clothes and toys today and no sweets. There will also be no places to pray as many mosques have collapsed.

Dozens of religious buildings in Mandalay are gone. This is partly due to the fact that – particularly for Islamic congregations – it has been near impossible to get official permits from the authorities to renovate the often dilapidated structures. Many stem from colonial times. I have seen in Yangon, how both Sunni and Shia congregations had to patch up holes in ceilings, stop water leaks and support crumbling walls without being able to properly renovate.

The landscape of Mandalay in particular will be changed and almost certainly, mosques will not be allowed to be rebuild. While human lifes are of course more important than buildings, these buildings have provided shelter and food for the less fortunate. Within their walls there was possibility for safe conversations, education was given for free in subjects not taught at public schools and in universities (not only about Islam, but also literature or English language), and they offered a space both for individual contemplation as well as for gathering and celebrating together.

Today, on Eid, it would be more than a nice gesture to donate to the victims in Myanmar – independently of their and our religious belief! I am copying the three links from my previous post below. In any case, make sure that your money does not go to the military by donating to small-scale initiatives instead.

1. Better Burma (https://lnkd.in/erq79zv6)

2. Advance Myanmar (https://lnkd.in/eQiC_8ut)

3. My PhD student from Mandalay, Nickey Diamond (Ye Myint Win), is collecting funds (https://lnkd.in/eNgZdGjD)

Please repost this and – if you can afford it – please help the people of Myanmar – they deserve it!

Thank you. ကျေးဇူးပါ။

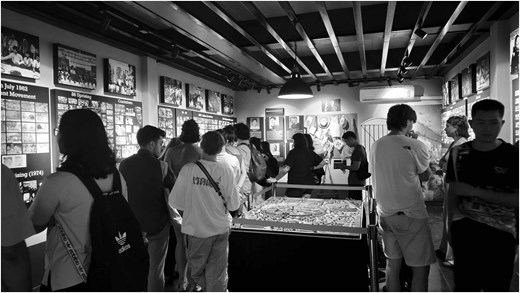

(photo: Judith Beyer. The famous “Nylon ice cream bar” in Mandalay, December 2009)

Help Myanmar!

The people of Myanmar are the most resilient people I have ever met.

But now, after this devastating earthquake, and with ongoing relentless attacks from the military since the attempted coup of 1 February 2021, they are exhausted and really need our support.

This is easier said than done. When a military dictator, notorious for shooting civilians in broad daylight, for bombing innocent children in their schools out of airplanes, for planting mines across the entire country which will cause suffering for decades to come, suddenly begs the “international community” for any humanitarian aid possible, we need to be very careful.

While international aid and financial support is of utmost importance at this moment, it can not go to the “state” of Myanmar, a structural position currently occupied by the military. As there is no legitimate government inside the country, there will be no way to ensure that the money reaches those who need it.

Instead, we can be sure that humanitarian aid will be diverted by the generals. So, how can you support those suffering?

Here are three initiatives, the first two are known for having done great work since at least the attempted coup, the third one is a personal recommendation:

1. Better Burma (https://lnkd.in/erq79zv6)

2. Advance Myanmar (https://lnkd.in/eQiC_8ut)

3. My PhD student from Mandalay, Nickey Diamond (Ye Myint Win), is collecting funds (https://lnkd.in/eNgZdGjD)

Please repost this and – if you can afford it – please help the people of Myanmar – they deserve it!

Thank you. ကျေးဇူးပါ။

Seeing beauty in details

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the Palm of Your Hand

And Eternity in an Hour.

(William Blake. Auguries of Innocence, 1803/1863)