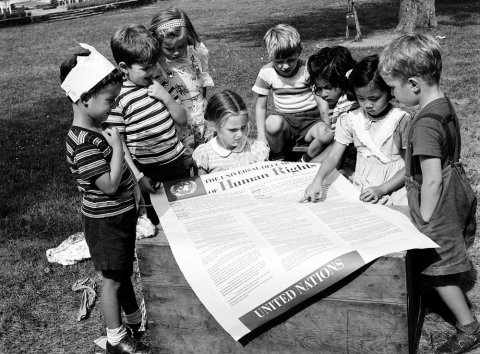

Before all other forms of membership, we are “all members of the human family”, as the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has specified. Thus, the international legal concept of crimes against humanity is crucial because all war crimes are predicated on the fact that those committing these atrocities are enabled once they succeed in establishing difference that makes us forget our human commonality.

We cannot but make do with what the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has called the imaginary order – the way in which we try to relate to others by looking for similarities and differences, mainly in order to acknowledge ourselves. We need the ‘other‘ to sustain ourselves as the I(ndividual) we imagine ourselves to be.

The imaginary order is the order of world-making in the sense of Hannah Arendt (1959) for whom the world is not ‘out there‘, but rather that which arises between people in discourse, as I will develop in an upcoming presentation. We have to keep engaging with others, irrespective of the fact that we will never really understand each other entirely. But we are obliged to keep trying. There is no other way.

“For the world is not humane just because it is made by human beings, and it does not become humane just because the human voice sounds in it, but only when it has become the object of discourse … We humanize what is going on in the world and in ourselves only by speaking of it, and in the course of speaking of it, we learn to be human” (Hannah Arendt, 1959, 24-25)

Human commonality is already there from the beginning, transcending all dichotomies, whereas difference is something we can only ever bring about consciously. What we have in common and what makes us human is that we are split by language, as Lacan argued. If we acknowledge this, we might be able to include the other not as an opposite ‘they’ but as part of our own unconscious: we are always other to ourselves first.