Our collaborative article “Exiled Activists from Myanmar: Predicaments and Possibilities of Human Rights Activism from Abroad“, published in the Journal of Human Rights Practice (Oxford University Press), is finally out! 🎉

I am very proud of the work that my colleague Samia Akhter-Khan, my two Ph.D. students Sarah Riebel and Nickey Diamond, another author from Myanmar (who has to use a pseudonym for reasons of safety), as well as myself have managed to achieve under very difficult circumstances.

This article was born out of necessity to engage with the topic of exile. None of us had ever wanted to study yet alone experience this existential state of being. The empirical material we draw on in this article stems from autoethnographic accounts (Nickey Diamond and Demo Lulin), semi-structured interviews and conversations with around forty exiled activists currently residing in Thailand, the US, the UK, Austria, and Switzerland (Samia Akhter-Khan and myself) as well as extensive ethnographic work with exiled activists in Thailand (Sarah Riebel).

In this article, we put forward the concept of the ‘exiled activist’ to highlight the predicaments and the possibilities that practicing human rights activism from abroad bring with it. From our analysis, we have developed three so-called ‘practitioner points’ that might guide INGOs, NGOs, states and other bodies to properly relate to exiled activists from Myanmar. These are:

1. Develop trauma-informed support systems for exiled activists by integrating psychosocial care and peer-based mental health resources into human rights programming and diaspora organizing.

2. Adapt partnership models to accommodate the shifting positionality of exiled activists, recognizing their need for secure digital platforms, flexible funding, and shared decision-making across borders.

3. Acknowledge and navigate political divisions within diverse groups of exiled activists – such as differing views on the National League for Democracy, the military, or the Rohingya – by avoiding assumptions of unity and instead fostering inclusive collaboration that respects diverse activist trajectories and lived experiences.

We have made our article openaccess so that everyone is able to download it. Currently, we are working on a shorter version in Burmese/Myanma, to also allow those who do not speak English to read about this important topic.

Thank you to all exiled activists who have participated in this study, trusted us and shared their stories – and to the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the support of scholars at risk over the last years!

Tag Archives: history

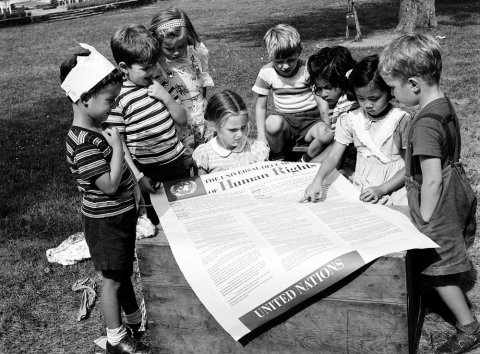

Crimes against commonality

Before all other forms of membership, we are “all members of the human family”, as the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has specified. Thus, the international legal concept of crimes against humanity is crucial because all war crimes are predicated on the fact that those committing these atrocities are enabled once they succeed in establishing difference that makes us forget our human commonality.

We cannot but make do with what the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has called the imaginary order – the way in which we try to relate to others by looking for similarities and differences, mainly in order to acknowledge ourselves. We need the ‘other‘ to sustain ourselves as the I(ndividual) we imagine ourselves to be.

The imaginary order is the order of world-making in the sense of Hannah Arendt (1959) for whom the world is not ‘out there‘, but rather that which arises between people in discourse, as I will develop in an upcoming presentation. We have to keep engaging with others, irrespective of the fact that we will never really understand each other entirely. But we are obliged to keep trying. There is no other way.

“For the world is not humane just because it is made by human beings, and it does not become humane just because the human voice sounds in it, but only when it has become the object of discourse … We humanize what is going on in the world and in ourselves only by speaking of it, and in the course of speaking of it, we learn to be human” (Hannah Arendt, 1959, 24-25)

Human commonality is already there from the beginning, transcending all dichotomies, whereas difference is something we can only ever bring about consciously. What we have in common and what makes us human is that we are split by language, as Lacan argued. If we acknowledge this, we might be able to include the other not as an opposite ‘they’ but as part of our own unconscious: we are always other to ourselves first.

La Flâneuse

Flâneuse [flanne-euhze], nom, du français. Forme féminine de flâneur [flanne-euhr], un oisif, un observateur flânant, que l’on trouve généralement dans les villes.

An incremental part of anthropology has always been photography for me. It can be used as an aide mémoire to simply remember where one has been or whom one has encountered on a particular day, thus substituting for fieldnotes. It can also be used as a methodological tool in order to detect the ‘minor modes’ in everyday life or in co-existence. A photograph can be scrutinized for its details, revealing more and more of them, every time one looks closer. But photography can also help express oneself when words fail. Rather than serving the eye, it serves the mouth that does not find the right words or ceases to speak alltogether. When used in this way, photography is neither only a method nor a product. It becomes a mode of existence in itself.

Femme vidant le canal

Une petite fille qui n’a aucun souvenir de la guerre exhorte les Français à s’en souvenir

14 millions de livres enfermés dans quatre tours pendant que les chercheurs travaillent sous terre

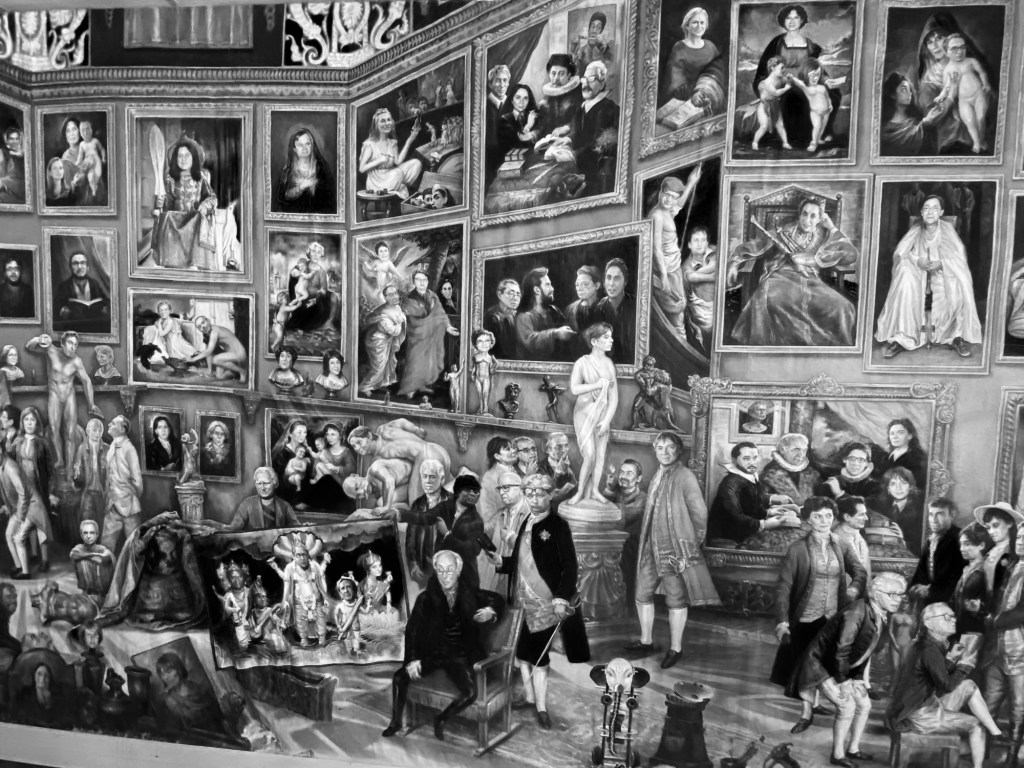

Partie d’une peinture murale de la faculté d’anthropologie de l’Université Paris-Nanterre, réalisée par un artiste déterminé.

Le Génie de la Liberté au sommet d’un arbre — illusions d’optique à la Place de la Bastille