My old school (Alte Landesschule Korbach) published an interview with me this month in their alumni journal. Sweet!

Category Archives: Allgemein

Teaching “Community” – BA-Seminar in Sociology at Konstanz

On the Shia community in Yangon, Myanmar

I posted a sound-bite from my recent fieldwork in Myanmar on Allegra this week.

I posted a sound-bite from my recent fieldwork in Myanmar on Allegra this week.

Here is the full text:

On December 2nd 2015, the Shia community in Myanmar celebrated Arba’een – the fourtieth day after Ashura. I recorded this martyr song around midnight in Myanmar’s former capital Yangon where I have been carrying out 12 months of ethnographic fieldwork between 2013 and 2016. That night, men and women joined a downtown procession of a tomb replica of Imam Hussain, the grandson of Mohammad. The Arba’een celebration is one of the largest Muslim celebrations worldwide, attracting around 25 million people in Karbala (Iraq) in 2015 alone.

In Yangon, however, the Shia community is very small. There are no official numbers; community leaders usually count the attendance at Ashura and Arba’een, the two most important memorial events of Shia. “We might be around 6000 in Myanmar,” one elder said, “but in Yangon, maybe around 3000 only.” During the yearly mourning period, which lasts for two months, the community gathers regularly in their two mosques in the downtown area. Women and men as well as various youth organizations have their own duties to perform and they organize seperate festive events. In 2015 and 2016, every week another donor came forward to pay for food to be prepared in the mosque on Fridays after juma, the weekly prayer meeting. The cooks, who are employed by the board of trustees of the mosque, prepared rice and chicken dishes for everyone and people took turns eating, making sure they finished their plate quickly to make space for new guests. Next to community members, also Buddhist monks, neighbours of various religious backgrounds, Sunni friends and the occasional tourists, who happened to pass by, were invited. Afterwards, milk tea was being served outside and people hung out to chat with each other.

The Shia community in Myanmar traces its origin back to either Iran or to India. Community members are well aware of each others genealogical backgrounds and frequently point to differences in their physical appearance to indicate the geographial origin of their great-grandparents who all had been brought from India to Burma (as the country was called until 1989). From 1840 onwards, the British colonizers had shipped thousands of “Indians” across the Bay of Bengal to help them in the administration of their final addition to the British Empire. Muslims from India had been under colonial governance already, they often spoke English well and knew how to interact with the British authorities. Rangoon, as the small town by the Andaman sea was called back then, quickly turned into an “Indian city” and was composed of people referred to as kula lu-myo in the Burmese language, literally “people who have crossed over” (meaning journeyed from India to Burma across the Bay of Bengal).

Members of the Shia community applied for a free land grant from the East India Company, an English, later British trade company that operated in India and Burma from the mid-18th century onwards. Their request was granted and two mosques were erected, both in the downtown area. Next to the two Shia mosques, Sunni mosques, Hindu temples and Christian churches were established in this period, turning Yangon into a multireligious place.

Although Myanmar is a de facto Buddhist state in which the majority of its population practices Theravada Buddhism, Yangon has retained its plural religious landscape until today.

Teaching this Winter Term 2016/2017

Community. Anthropological and Sociological Perspectives on Vergemeinschaftung

Project Seminar (4 SWS with Fieldwork Component, in German); University of Konstanz

The English term ‘community’ has been established in the German language as jargon. It is usually used in combination with various adjectives and thus covers a wide range of meanings: communities can be imagined, virtual, indigenous, radical, religious, sustainable, or alternative, to name just a few examples.

But what exactly do we mean when we use the term in the academic context? What are the important shifts in meaning that have occurred in the last two centuries, and why is the notion still relevant today? After reading classic and current literature on the topic, students will carry out fieldwork in the Konstanz area with a group that identifies itself as a community. Using ethnographic methods such as participant observation, the aim of this course is to collect, interpret and analyze data from one’s own fieldwork in order to gain a better understanding of how social organizations and social relations are being achieved, maintained, and challenged. The course is accompanied by a methods training, data sessions, and a final meeting in which students present and receive feedback on their field report.

Neues Masterprogramm “Ethnologie und Soziologie” an der Universität Konstanz

Aus der aktuellen Pressemitteilung der Universität Konstanz:

“Lange wurden Berührungspunkte zwischen Ethnologie und Soziologie vorwiegend in Fragen nach Entwicklung, Modernisierung, Globalisierung und Migration gesehen. In jüngerer Zeit kam es vermehrt auch zu methodischen Diskussionen, die durch ein gemeinsames Interesse am Forschungsstil der Ethnographie gekennzeichnet sind. Doch oft bleibt es bei einem kurzen Verweis auf Konstellationen der Wissenschaftsgeschichte, in denen die Unterscheidung zwischen den beiden Fächern keine zentrale Rolle spielte, so etwa in der „Chicago School“ oder bei Bezügen auf Gründerväter der Sozialtheorie wie Marcel Mauss oder Émile Durkheim und neuere Grenzgänger wie Pierre Bourdieu oder Bruno Latour, die mitunter von Vertretern beider Disziplinen für sich beansprucht werden. Insgesamt bleibt die systematische Zusammenführung von Allgemeiner Ethnologie und Allgemeiner Soziologie in der deutschen Wissenschaftslandschaft allerdings weiterhin ein Desiderat”

(der vollständige Text ist unter http://bit.ly/1X3crc7 einsehbar).

Zusammen mit Prof. Dr. Thomas Kirsch habe ich im vergangenen Jahr an dem neuen Masterprogramm “Ethnologie und Soziologie” gearbeitet – im kommenden Wintersemester 2016/2017 kann es endlich losgehen.

Der Master richtet sich an alle Studierende der Ethnologie, Soziologie oder benachbarter Fächer, die kleine Seminare mögen, selbst forschen wollen und in einer der schönsten Gegenden Deutschlands – im Dreiländereck angrenzend zu Österreich und der Schweiz (Bodensee! Zürichnah!) studieren wollen.

In dem zweijährigen Studium ist eine Lehrforschung, die sich über zwei Semester erstreckt, fest eingeplant. Diese kann sowohl in Deutschland als auch im Ausland stattfinden. Die Ethnologie Konstanz hat mittlerweile Expertise in Afrika (Südafrika, Zambia) und Asien (Kirgistan, Myanmar) vorzuweisen und betreut deutsch- wie englischsprachige Abschlussarbeiten.

Anmeldungsfrist ist der 15. Juli 2016. Hier geht es zur website: https://www.soziologie.uni-konstanz.de/studium/studiengaenge/ethnologie-und-soziologie-ma/

Yangon Photography

The spider

The thought crept into my mind today and refused to let go of my brain. It said “What if we have no f*ing clue?” Going to bed with images of crying fathers holding their children – ‘Are they dead? Oh thank God, only sleeping!’ – , waking up with stories of rotten bodies, locked into a van used for transporting poultry. Heaps of rotten meat. This is not happening in Syria. This is Syria happening in Europe. Those who survived are here. But what if the war that was carried out on their backs will follow them? Did it ever occur to you that Europe is not facing a “refugee crisis” but is already part and parcel of several wars that have forced hundreds of thousands of human beings – like you, like me – to leave everything behind to save bare life? Their crisis is our crisis, but we don’t pay the price yet that they have already paid. But we might, if we don’t act.

I feel I am responsible at least in part for their desperation. Because as a German citizen I have voted for a certain party, have legitimized a certain type of government, because my taxes are used in ways I cannot control any more. Because I live in an area of Germany, which is profiting from the military industry that is located all around me; that exports weapons, drones and military equipment to I don’t know where. The thing is, there are people who do know, who are responsible, who profit, who might even believe that this is needed for ‘security’, ‘stability’ or – probably the most honest reason – because a lot of German citizens earn their money with these kinds of endeavours.

Recent demonstration in Constance, Germany against the military industry located on the shores of Lake Constance in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Photo credit: Felix Girke

This morning at a local farmer’s market in my small picturesque town in Germany an elderly woman approached the mostly well-off clientele with a request to donate whatever they could afford for “refugees from Syria.” She offered small bouquets of rosemary in return which she had collected from her garden, I overheard. I felt anger. In fact, I became so angry, I had to turn away. What made me angry was not her compassion and her initiative of wanting to “do something.” Where would we be without people like her? Or so many others in Greece, Italy, Jordan, Serbia – all devoting their lives to ease the suffering of thousands. My current anger is directed towards the nebulous “system”, towards “those in power” whom I consider responsible … but how do you hold “them” accountable? There is no way to trace the origin of a ‘crisis’, which has reached the scale of what we are witnessing right now, everyday. How can you prevent our grandchildren from accusing us that ‘they knew, but they did not do anything’ – Germany has been there before. So what to do? Donate money, children’s clothes and food products? Check. Write letters to politicians? Check. Be thankful for every calm and sunny summer day and hug your own child a little longer? Check. But still. The thought won’t go away: We have no f*ing clue how to make this stop.

Looking outside my window, I see a large spider spinning its web, waiting patiently for prey. I still want to believe we are not trapped. We are the net.

Update on September 3, 2015:

In the last days I have began to communicate with a couple of people who do amazing work in different parts of Greece and Germany right now. All work privately and have financed their support for refugees through crowdfunding. Please consider helping them, and donate whatever you can .

1. Help for refugees in Molyvos (you can also contact molyvosrefugees[at]gmail.com)

5. Jillian York (she collects money and transfers it to Budapest so that technical supplies such as cell phone chargers can be bought for refugees currently stuck at the train station; also: check her own page for another list)

6. Eric and Philippa Kempson (they have set up amazon wishlists with important food products, medical supplies, clothes,…)

*****

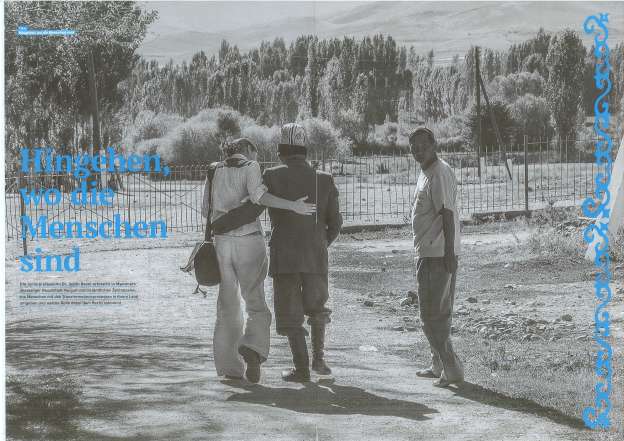

Article about my work in Kyrgyzstan and Myanmar

Rights and Responsibilities.

I wrote a blog post for allegralaboratory.net on Anonymous Peer Review and how it is often achieving the opposite of what it is supposed to. With helpful hints on how to review better!